Slum Rehabilitation in India: Best Practices and New Challenges

Executive summary (200 words)

India’s urbanisation will add tens of millions of residents to cities over the next decade, even as the country continues to grapple with legacy housing deficits and climate risks. “Slums” (in India’s official usage: notified, recognised and identified settlements) remain a large share of urban housing stock. The last full count (Census 2011) recorded ~65 million people living in slums; updated nationwide figures have been hard to establish in the absence of the 2021 Census. Maharashtra Slum Resident Association

Since the mid-1990s, India has tried multiple models: cross-subsidised in-situ redevelopment (most famously via Mumbai’s Slum Rehabilitation Authority, SRA), relocation to EWS housing on peripheral land (e.g., Tamil Nadu), community-led upgrading and tenure security (e.g., Odisha’s JAGA Mission), and demand-side subsidies under Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana-Urban (PMAY-U). PMAY-U sanctioned ~1.18–1.23 crore urban homes between 2015 and 2024 and has been extended to complete sanctioned houses through 31 December 2025; central assistance norms remain ₹1 lakh per ISSR unit and ₹1.5 lakh per BLC/AHP unit. Yet the dedicated in-situ slum redevelopment (ISSR) vertical accounts for a very small share of completions. Press Information Bureau+1The Economic TimesPMAY-Urban+1

The most successful Indian experiences pair secure tenure, trunk infrastructure, and participatory planning with viable finance (cross-subsidy, TDR/FSI, VGF) and strong institutions. This article synthesises what’s working (Mumbai SRA densification with reforms, Ahmedabad’s “Parivartan” slum networking, Odisha’s citywide land-tenure approach, community sanitation alliances) and what’s not (weak maintenance, peripheral displacement, data gaps, climate risk), and proposes a 10-point playbook for 2025–2030.

1) Why slum rehabilitation matters now

- Scale & definitions. India’s Census defines three slum types (notified, recognised, identified) and counted ~13.7 million slum households (≈65 million people) in 2011. Without a 2021 Census, planners rely on administrative and programme dashboards, complicating citywide planning and finance. Maharashtra Slum Resident Association

- Urban poverty & informality. Slums are typically close to jobs but lack tenure security, resilient housing, and services, exposing residents to eviction cycles, floods, fire, and heat risk. Evidence from multiple cities links service deficits to public-health costs and exclusion. World Bank

- SDG 11.1 (adequate, safe and affordable housing), climate adaptation, and productivity all place rehabilitation at the core of India’s urban strategy.

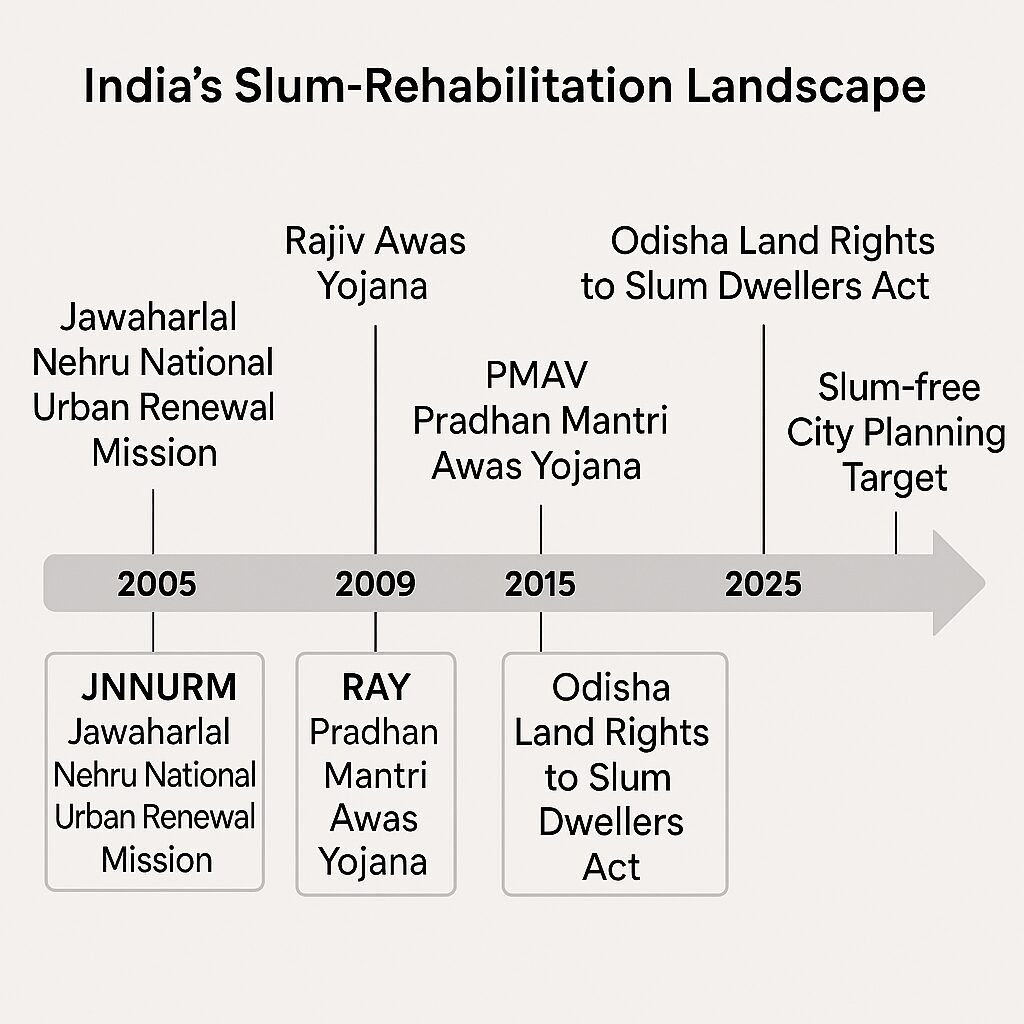

2) The policy arc: from projects to systems

Early programmes focused on sites-and-services, BSUP/IHSDP (JNNURM), Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY), and state-led clearance boards (e.g., Tamil Nadu). Since 2015, PMAY-Urban has framed four verticals—ISSR (in-situ slum redevelopment), AHP (affordable housing in partnership), BLC (beneficiary-led construction), and CLSS (credit-linked subsidy). As of mid-2024, PMAY-U reported ~1.18–1.23 crore houses sanctioned, ~80–90 lakh completed, with the Union government extending timelines to complete sanctioned homes till 31 December 2025 and re-emphasising BLC/AHP. Central assistance norms are ₹1 lakh/house under ISSR and ₹1.5 lakh/house under AHP/BLC; CLSS delivered interest subsidies up to ₹2.67 lakh for EWS/LIG. Press Information Bureau+1The Economic TimesPMAY-Urban+1

Multiple analysts note ISSR’s small share within PMAY-U relative to BLC/AHP (i.e., most slum households have benefited indirectly via other verticals rather than direct ISSR). Some commentary also noted policy recalibration in 2024–25 that de-emphasised ISSR. CSEPORF Online

Affordable Rental Housing Complexes (ARHCs) launched in 2020 aimed to repurpose government/PPP housing for migrants and urban poor, but uptake has been modest and uneven across cities. ircwash.org

3) India’s leading models—what’s working

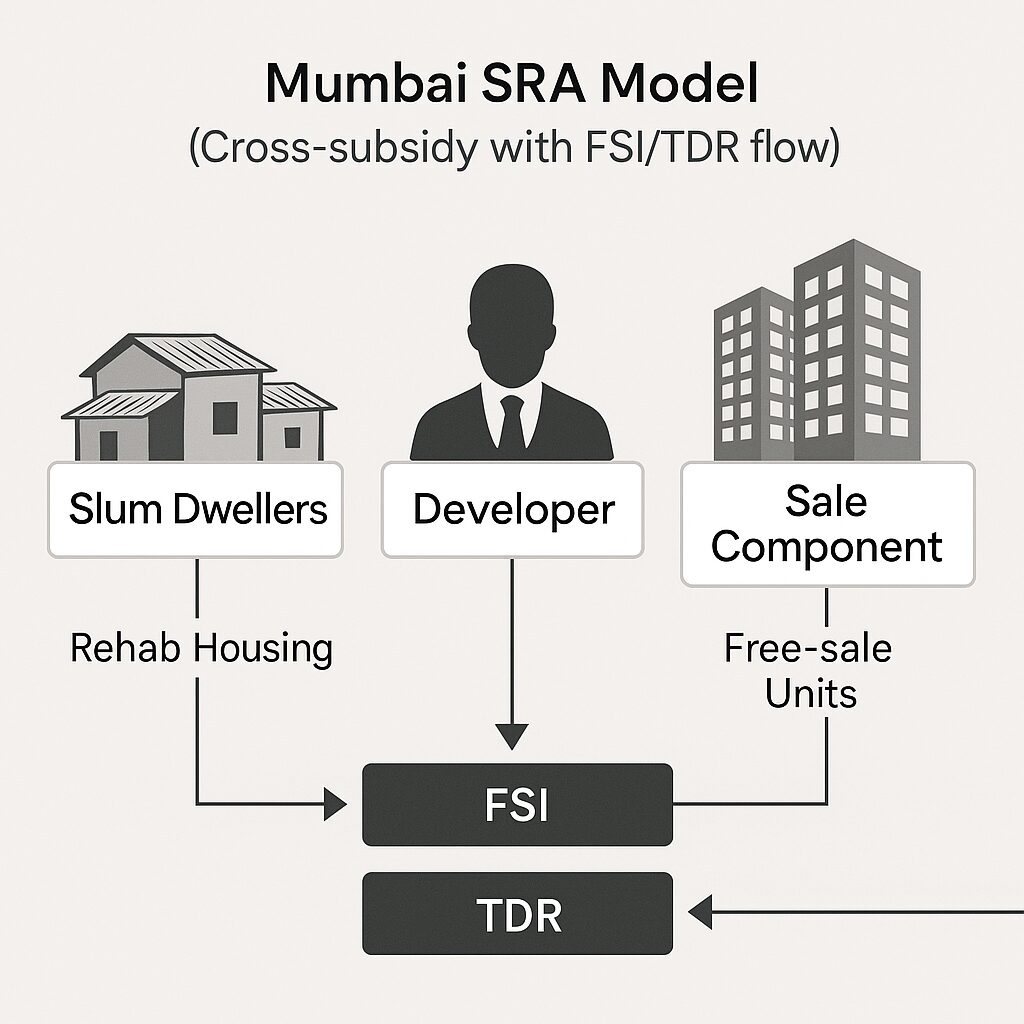

3.1 The Mumbai SRA model (cross-subsidy + FSI/TDR)

How it works. Developers relocate eligible slum households to free rehab units on the same parcel (or nearby), funded by sale of additional FSI (on- or off-site via TDR) to the formal market. Over time, rehab unit sizes rose—from 225 sq ft to ~300–322 sq ft, with some special schemes now promising 350 sq ft (e.g., Dharavi). SRA is reforming stalled projects, digitising surveys, and strengthening rent compensation to PAPs. Hindustan TimesThe Times of India+1

Scale & updates. Mumbai targets 5 lakh SRA homes by 2030, roughly double the cumulative output since 1996 (~2.36–2.75 lakh units, depending on the cut-off date and dataset). Current reforms include quick approvals, drone/biometric surveys, and recovery of dues from errant developers. The Times of IndiaCitizen Matters

Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP). The DRP proposes 350 sq ft homes for pre-2000 eligible residents, with specific entitlements for different cut-off periods; policy pages show 350 sq ft (≤1 Jan 2000) and 300 sq ft for later bands with hire-purchase options. New directives also contemplate a 50:50 split of land between rehab and sale, alongside off-site rental solutions for post-2011 residents. Dharavi Redevelopment ProjectThe Times of India

Lessons. The model can unlock land value to pay for rehab; success hinges on clear eligibility cut-offs, credible surveys, robust escrow for rent/transition, and O&M governance post-handover to avoid “vertical slums.”

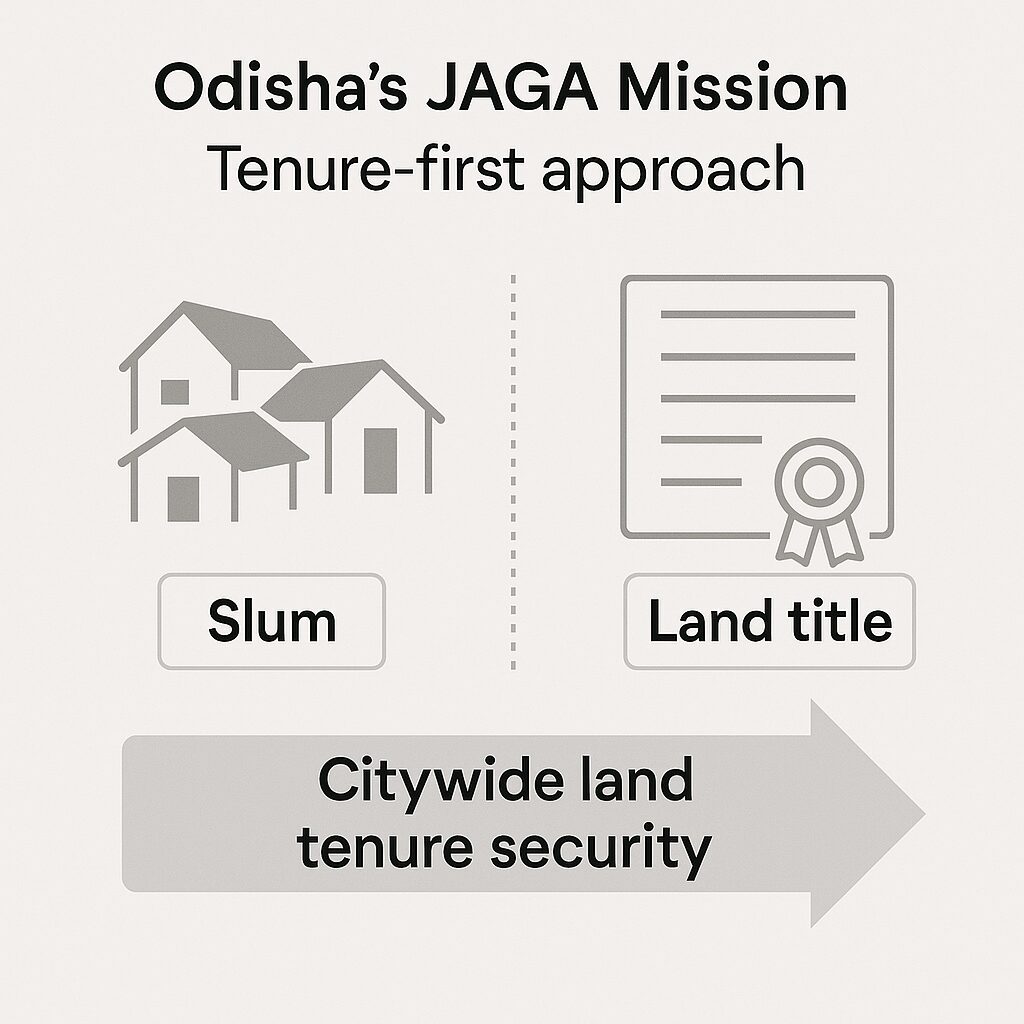

3.2 Citywide land-tenure security: Odisha’s JAGA Mission

Odisha’s JAGA Mission provides land-rights certificates to slum households, coupled with infrastructure upgrading and social development in ~2,900+ settlements, often cited as one of India’s most scalable, inclusive approaches. Secure tenure catalyses self-investment, improves access to services and finance, and lowers eviction risk. MagicBricksHindustan Times

3.3 Community-led upgrading & sanitation alliances

Mumbai’s SPARC–NSDF–Mahila Milan alliance scaled community-designed toilets with municipal partnerships—an approach replicated across Indian cities. Community stewardship improved maintenance, safety (especially for women and children), and cost recovery. SAGE JournalsEnvironment and Urbanization

3.4 The Ahmedabad “Parivartan” (Slum Networking Programme)

A partnership among AMC, NGOs and communities upgraded water, sanitation, drainage, paved lanes, street lighting, solid waste systems, and community infrastructure across dozens of slums. Evaluations recorded improved health access and service reliability along with cost-sharing and community maintenance—an important complement to house construction. World Bank

3.5 State mass-housing (Tamil Nadu) + relocation

Tamil Nadu’s urban housing board (now TN Urban Habitat Development Board) has delivered large EWS housing stocks (e.g., Perumbakkam). This provides speed and scale, but peripheral relocation without adequate livelihoods, transit, schools, and clinics can undercut welfare; governments are now retrofitting social amenities and fixing defects. Citizen MattersMagicBricks

3.6 Legal due-process gains

Judicial developments—e.g., Sudama Singh in Delhi—require meaningful rehabilitation planning before evictions; recent Delhi HC rulings re-emphasise policy-based eligibility and due process (but also clarify that encroachers cannot indefinitely hold public land during assessment). Olga Tellis (1985) affirmed the right to livelihood under Article 21. Together, these shape the procedural framework for humane rehabilitation. Indian KanoonCPRThe Times of India

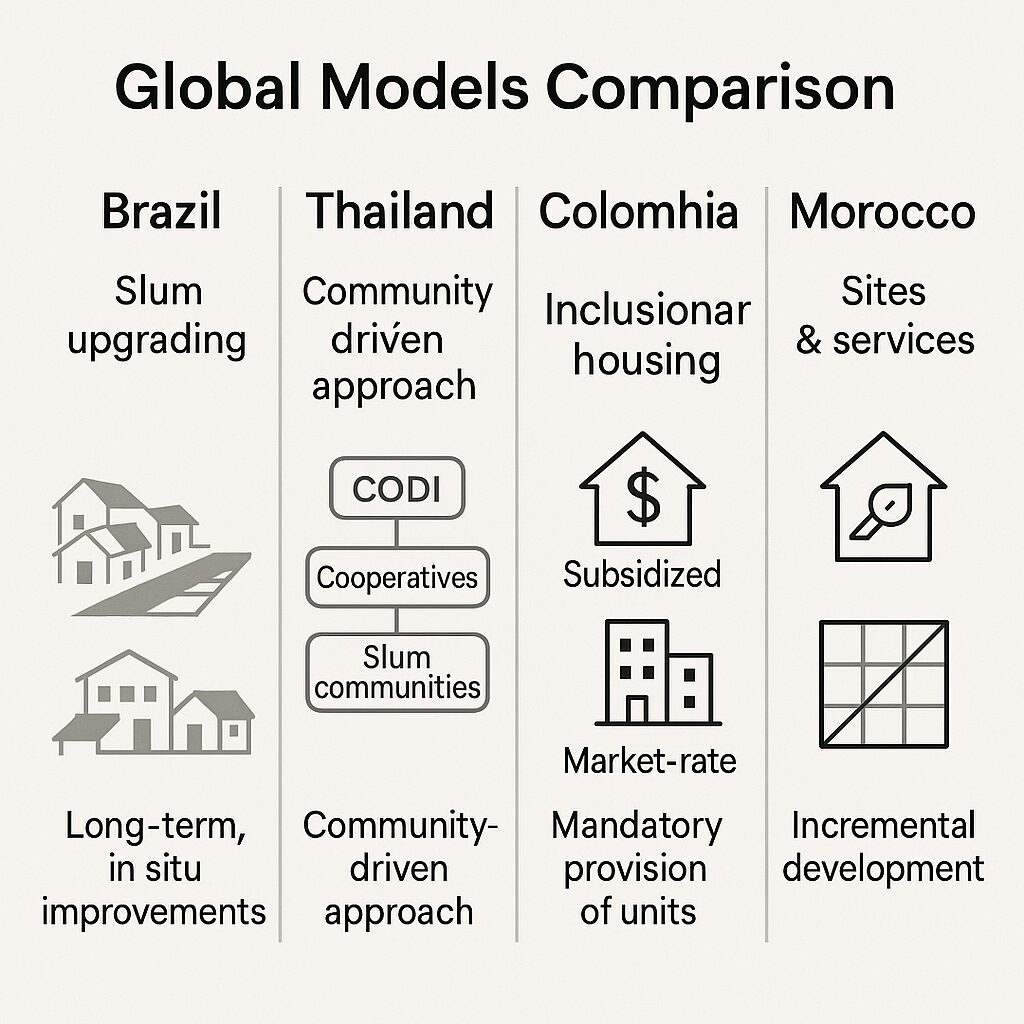

4) Global comparisons and lessons

- Brazil (Rio de Janeiro, Favela-Bairro): Large-scale upgrading integrated favelas into the formal city grid (infrastructure, public spaces). Long-term assessments show improved access and urban form but also highlight maintenance shortfalls and the need for social services and continued funding. World Bankpublications.iadb.orgblogs.iadb.org

- Thailand (Baan Mankong, CODI): Citywide, people-driven upgrading that channels finance to community groups for re-blocking, on-site reconstruction, and collective tenure; widely cited as a best-practice model for participation and flexible finance. web.codi.or.thMIT Press DirectWorld Resources Institute

- Colombia (Medellín, “social urbanism”): Cable-car transit integrated informal hillsides with the metro network; paired with public space, education and safety programming. Results include better access and social inclusion—but studies caution about gentrification dynamics around stations without safeguards. World Resources InstituteScienceDirectprojekter.aau.dk

- Morocco (Villes Sans Bidonvilles): A nationwide program combining resettlement, serviced plots and upgrading; evaluations underscore the need to protect affordability and livelihoods during transitions. World BankSpringerLink

Implication for India: The gold standard blends tenure, services, mobility access, and livelihoods—not “housing only.” Citywide, programmatic instruments outperform one-off projects.

5) New challenges in 2025 (and why the old playbook isn’t enough)

- Data gaps & eligibility disputes. With no 2021 Census, cities depend on patchy surveys; disputes over cut-off dates (e.g., 2000/2011 bands in Mumbai) feed litigation and delays. Digital, geo-referenced, publicly auditablesurveys (like Dharavi’s twin digital model) are essential. The Times of India

- Stalled projects, rent arrears, and trust deficits. Maharashtra/SRA has tightened rent escrow and recovery from developers’ assets to protect PAPs, and is tendering stalled schemes directly. This must become standard (escrow + milestones + personal guarantees). The Times of India+1

- Quality & O&M: preventing “vertical slums.” Early SRA towers lacked sinking funds, lifts/generators maintenance, or robust RWAs. States now plan redevelopment of early-year blocks under cluster models, but it requires enforceable, funded O&M frameworks from day one. The Times of India

- Peripheral relocation & social costs. Where in-situ isn’t feasible, relocation must be networked—with bus/metro passes, last-mile mobility, school admissions, anganwadis, clinics, and livelihood support. Evidence from Chennai shows the risks when social infrastructure lags. MagicBricks

- Climate & disaster risk. Heat waves, intense rainfall, riverine and coastal floods disproportionately affect slums. Design standards (elevated plinths, floodable ground floors, cool roofs, cross-ventilation) and district-scale drainage must be mainstreamed, not piloted.

- Financial viability under higher unit sizes. Rehab sizes have risen (e.g., 300–322 sq ft typical; 350 sq ft for Dharavi). Each increment stresses cross-subsidy math; this requires FSI/TDR recalibration, viability-gap funding (VGF), and monetisation of public land at programme—not project—level. Hindustan TimesDharavi Redevelopment Project

- Migrant housing & rentals. ARHCs remain under-deployed; Model Tenancy Act (MTA) offers a framework (e.g., security deposit cap of two months’ rent for residences) to de-risk small landlords and expand affordable rental stock near jobs. Cities need to localise MTA rules and link ARHCs to transit. ircwash.orgPRS Legislative Research

- Land scarcity & brownfield constraints. Rehabilitation must align with DCPR/UDCPR and land-use plans, reserving amenity FSI and open spaces, and ensuring social-mixing (not mono-income blocks). MMRDA Maharashtra

- Institutional capacity. ULBs need PMUs with procurement, contracts, social safeguards, and ESG/SDG reporting—so that upscaling doesn’t outpace oversight.

- Rights and due process. Courts continue to insist on policy-compliant rehabilitation, but also push back against indefinite occupation of public land during disputes—raising the quality bar for transparent surveys and appeal mechanisms. The Times of India

6) Financing the feasible (not just the ideal)

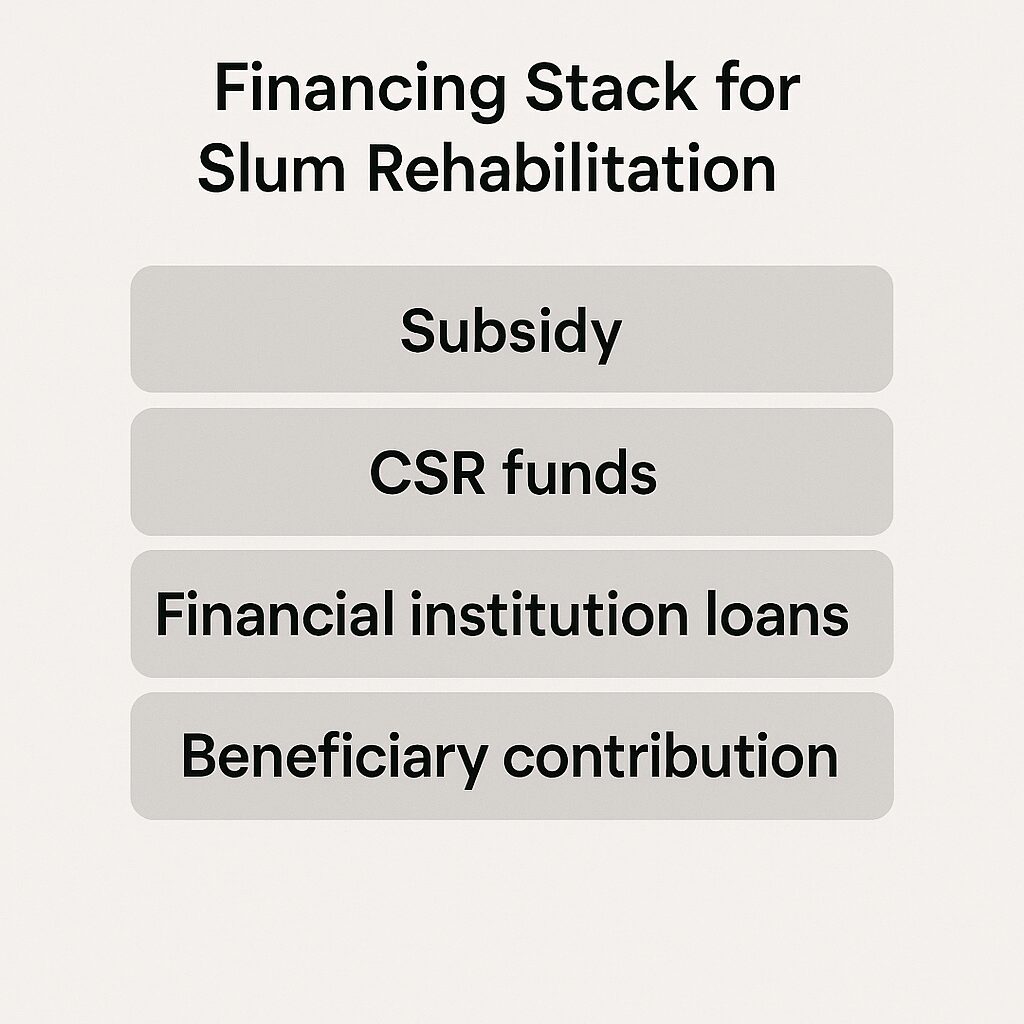

A robust package stacks multiple instruments:

- Cross-subsidy + market sale FSI/TDR. The SRA template remains core; recalibrate sale-FSI premiums to cover rising rehab specs and on-site social amenities. Tie occupancy certificate to a funded O&M plan.

- PMAY-U assistance & VGF. Budget for ₹1 lakh/ISSR unit and ₹1.5 lakh/AHP-BLC central assistance; use state/ULB VGF to close gaps where land values are weak. Press Information BureauPMAY-Urban

- Land value capture (LVC). Capture betterment from adjoining infrastructure (e.g., metro stations) via impact fees/surcharges; ring-fence proceeds for rehab O&M and community facilities.

- Municipal finance. Leverage municipal bonds, pooled finance, and project-linked SPVs with escrowed revenues; green/climate bonds for resilient design features (cool roofs, rainwater harvesting, micro-grids).

- ARHC + rental vouchers. In high-cost cores, rental subsidies for time-bound periods (e.g., construction) prevent livelihood disruption; align with MTA to de-risk landlords. ircwash.orgPRS Legislative Research

- CSR and philanthropy can fund community facilities (crèches, digital labs) and skills programmes that public budgets often under-provide.

7) Design and implementation standards that actually work

Unit & building design

- Area: Target 300–350 sq ft with flexible partitions (sleeping lofts, work nook); ensure daylight, cross-ventilation, kitchens with adequate exhaust, and balconies for drying/thermal comfort.

- Resilience: Elevated plinths or stilted ground floors in flood-prone zones; cool roofs, high-albedo finishes, shading, courtyard typologies; fire safety with two stairwells, refuge areas, and tested materials.

- Universal design: Step-free access, wider corridors, handrails, ramps and lifts; age-friendly and child-safe features.

Neighbourhood & services

- 15-minute city logic: primary schools, anganwadis, PHCs, PDS shops, and last-mile transit within a short walk; lock in space for community halls and skill centres.

- Water-sanitation: Citywide network upgrades plus decentralised wastewater where networks lag; lessons from SPARC’s community sanitation on design + upkeep. SAGE Journals

- Solid waste: Door-to-door collection; MRFs; decent work conditions for informal waste pickers.

Social and economic integration

- Livelihoods first: On-site kiosks/SME spaces, multi-level markets, and maker spaces; temporary rental stipends during transition to avoid income shocks.

- Phasing & right of return: Clear construction phasing, nearby transit accommodation, and guaranteed right-of-return to in-situ units where feasible.

Operations & maintenance

- Sinking fund baked into DPRs; five-year O&M support tapering to RWAs/Federations; performance-based facility management contracts.

8) Governance: from one-off “projects” to citywide “programmes”

- Citywide surveys: Mandate GIS/photogrammetry + household biometrics; publish draft beneficiary lists for objections; independent social audit before finalisation (Dharavi’s twin digital approach points the way). The Times of India

- Single-window clearances: Time-bound approvals with deemed-approval clauses, online dashboards (SRA’s “Mitra Vaani” and data tables show movement). sra.gov.in

- Contracts that protect households: Escrow for rent/transition payments, milestone-linked release, and clawbacks; fast-track panels to replace non-performing developers (as SRA/ULBs have begun to do). The Times of India

- Safeguards & grievance redress: On-site facilitation centres, gender desks, labour compliance audits, and community oversight committees.

- Open data & KPIs: Publish KPIs monthly (tenure issued, units occupied, rent paid, defects resolved, O&M status, school enrollments post-move).

9) Best-practice caselets (India)

Mumbai SRA 2.0 (institutional reforms). The authority reports 3.34 lakh units under development, ~2.36–2.75 lakh delivered cumulatively; a new push targets 5 lakh units by 2030 with stronger rent protections and direct contracting of stalled projects. The Times of India

Dharavi Redevelopment (entitlement clarity). Official pages lay out eligibility bands and 350/300 sq ft entitlements along with hire-purchase options—important for trust and transparency. Dharavi Redevelopment Project

Odisha JAGA (tenure-first). Land-rights certificates across ~2,900+ settlements show how tenure catalyses self-help upgrading and service connections; widely studied and recognised. MagicBricks

Ahmedabad Parivartan (infrastructure + maintenance). A citywide framework for slum networking, with cost-sharing and community-led O&M, improved WASH and public lighting; replicable at ward scale. World Bank

Community sanitation alliances (Mumbai). Two decades of community-designed, built and managed toilets demonstrate how participation raises service quality and dignity, particularly for women and children. SAGE Journals

Delhi’s due-process jurisprudence. Sudama Singh (2010) and subsequent cases require a rehabilitation exercise prior to eviction; 2025 Delhi HC rulings emphasise that while rehabilitation must follow policy, encroachment cannot block essential works indefinitely—raising the bar for credible surveys and fair lists. Indian KanoonThe Times of India

10) A 10-point playbook for 2025–2030

- Census-grade slum baselines within 12 months. Every million-plus city should conduct a Dharavi-style twin digital survey—satellite + door-to-door—publishing provisional beneficiary lists for objections, with third-party audits and a grievance portal. The Times of India

- Tie approvals to funded O&M. No building permit without a five-year O&M plan and escrowed sinking fund. Tie occupancy certificates to demonstration of lift maintenance contracts, AMC for pumps/gensets, and RWA training.

- Make in-situ the default; relocation the last resort. Where relocation is unavoidable, bundle it with mobility (bus/metro passes), school seats, clinics, and livelihood spaces—before handover—to avoid Perumbakkam-style dislocations. MagicBricks

- Recalibrate FSI/TDR & premiums to new entitlements. If rehab floors grow to 350 sq ft, offset with higher sale FSI where feasible, limited tradable TDR, and state VGF in low-value markets. Hindustan Times

- City ARHC pipelines + MTA adoption. Line up surplus government housing, factory dorms, and PPP stock into ARHCs near job centres; implement Model Tenancy Act rules to de-risk small landlords and scale affordable rentals. ircwash.orgPRS Legislative Research

- Climate-smart design code for rehab. Update DCR/UDCPR with cool roofs, shaded corridors, cross-ventilation, elevated plinths, floodable ground floors, and EV-ready wiring; certify “resilient rehab” with green ratings and climate-bond eligibility. MMRDA Maharashtra

- Developer discipline + PAP protections. Standard escrow for PAP rent and shifting allowances; black-list non-performers; allow ULBs to re-tender stalled projects and attach promoters’ assets to recover dues, as SRA now does. The Times of India+1

- Community institutions. Fund women’s savings groups and settlement federations to co-manage toilets, waste, and community halls; draw on SPARC/NSDF practices for scale and accountability. SAGE Journals

- Transparent benefit portability. A single Urban Housing ID should track eligibility, benefits received (BLC/ISSR/ARHC), and right-of-return; reduce duplication and disputes.

- Measure what matters. Publish ward-level KPIs monthly: units occupied (not just sanctioned), time in transit accommodation, school enrolment retention, women’s safety incidents, O&M compliance, flood/heat incidents, and livelihood outcomes 6–12 months post-move.

11) Frequently asked implementation questions

Q1. Is ISSR financially viable outside marquee markets?

Yes—with a stack: adjusted sale-FSI, limited tradable TDR, off-site monetisation, and state/ULB VGF. Where values remain low, prioritise tenure + services (JAGA-style) and AHP/BLC to upgrade in place. Press Information Bureau

Q2. How big should units be?

Policy trends point toward 300–322 sq ft in most schemes; special projects (e.g., Dharavi) go to 350 sq ft. Balance dignity with viability; invest savings into better common areas and long-life O&M. Hindustan TimesDharavi Redevelopment Project

Q3. What about migrants who don’t meet cut-offs?

Use ARHCs, dormitory-style hostels near employment nodes, and MTA-enabled micro-rental markets with deposit caps (2 months for residences) to de-risk landlords. ircwash.orgPRS Legislative Research

Q4. How do we avoid “vertical slums”?

Fund O&M from day one; professional FM; resident training; enforce defect liability; and establish a repair reserve indexed to inflation and energy costs—then monitor publicly. (SRA’s plan to rebuild early-year blocks is a cautionary signal.) The Times of India

12) A realistic road map (2025–2030)

Year 1: Complete citywide digital surveys; freeze eligibility lists; publish rehab pipelines ward-wise; pilot resilient-rehab code in two wards; put O&M escrow in every DPR.

Years 2–3: Scale in-situ projects with end-to-end rent escrow and social-amenity phasing; convert vacant EWS stock to ARHCs near transit; roll out MTA rules.

Years 3–5: Retrofit early-year blocks; institutionalise community O&M and grievance cells; expand climate-bond financing for cool roofs, micro-grids and flood-safe design; align impact fees to fund rehab amenities.

Outcome metrics: Not just houses completed, but houses occupied and sustained (three-year O&M compliance, school retention, commute time, and reduced heat/flood incidents).

13) References (selected)

- Census & definitions: Office of the Registrar General—Census 2011 slum definitions and counts. Maharashtra Slum Resident Association

- PMAY-U progress & norms: PIB; PMAY-U guidelines/website; PMAY-U extension to 31 Dec 2025; analysis of vertical performance. Press Information Bureau+1PMAY-Urban+1

- ARHC & MTA: ARHC scheme status; Model Tenancy Act deposit caps. ircwash.orgPRS Legislative Research

- Mumbai SRA & Dharavi: SRA outputs/reforms; Dharavi entitlements; recent directives; unit size evolution. The Times of India+1Dharavi Redevelopment ProjectHindustan Times

- Odisha JAGA: Land-rights approach and scale. MagicBricks

- Ahmedabad Parivartan: World Bank briefs and evaluations. World Bank

- Community sanitation: SPARC/NSDF/Mahila Milan long-term partnerships. SAGE Journals

- Due-process jurisprudence: Sudama Singh (Delhi HC); 2025 Delhi HC ruling on encroachment vs. rehabilitation; Olga Tellis overview. Indian KanoonThe Times of IndiaESCR-Net

- Global programmes: Rio Favela-Bairro; Thailand Baan Mankong; Medellín Metrocable case evidence. World Bankpublications.iadb.orgWorld Resources Institute+1

14) Closing note

The core insight from three decades is simple: houses alone don’t rehabilitate. Secure tenure, decent services, resilient design, affordable mobility, and funded O&M—held together by credible surveys, enforceable contracts, and community institutions—do. If India can lock those pieces into a single, citywide programmatic frame, slum rehabilitation can shift from episodic projects to durable, dignified urban inclusion.

15) Glossary of Key Terms & Abbreviations in Slum Rehabilitation (heading + infographic)

1. SRA – Slum Rehabilitation Authority

A statutory authority established in Maharashtra (1995) to implement slum rehabilitation schemes, particularly in Mumbai.

2. SRD – Slum Redevelopment Scheme

A scheme launched in Mumbai before SRA, where private developers redeveloped slums by giving free housing to slum dwellers and using remaining land for commercial purposes.

3. FSI – Floor Space Index

Also called FAR (Floor Area Ratio). It is the ratio of the total floor area built on a plot to the total size of the plot. Higher FSI allows taller or denser buildings.

4. DCR – Development Control Regulations

Rules governing land use, building height, open spaces, and FSI in cities. DCR 33(10) in Mumbai relates specifically to slum rehabilitation.

5. PPP – Public–Private Partnership

A model where government and private developers jointly implement slum rehabilitation projects. The government facilitates approvals/land, and private developers fund construction in return for incentives.

6. JNNURM – Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission

A Government of India programme (2005–2014) to improve urban infrastructure and housing, including slum upgrading.

7. RAY – Rajiv Awas Yojana

A Government of India scheme (2011) aimed at making India slum-free by providing housing to the urban poor.

8. PMAY – Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana

Launched in 2015, it is India’s flagship housing scheme with the goal of “Housing for All by 2022/24,” including slum rehabilitation and affordable housing.

9. BSUP – Basic Services for the Urban Poor

A sub-mission under JNNURM focused on providing water supply, sanitation, and housing for the urban poor.

10. ISDP – Integrated Slum Development Programme

A scheme focusing on holistic development of slum areas through housing, basic services, and livelihood improvement.

11. NGOs – Non-Governmental Organisations

Civil society organisations that play a key role in mobilising communities, ensuring fair practices, and supporting implementation of rehabilitation projects.

12. CBOs – Community-Based Organisations

Local groups formed by slum residents to represent their collective interests in planning and rehabilitation projects.

13. Tenable vs. Untenable Slums

- Tenable slums: Can be upgraded in-situ (on the same land) with basic infrastructure.

- Untenable slums: Unsafe (on drains, highways, airport land, etc.) and must be relocated.

14. In-Situ Rehabilitation

A method of redeveloping slums on the same land where residents currently live, instead of relocating them to distant areas.

15. Transit Camps

Temporary housing provided to slum dwellers while their homes are being redeveloped under rehabilitation schemes.

16. TDR – Transfer of Development Rights

A mechanism that allows developers to receive additional construction rights on another piece of land in exchange for rehabilitating slums.

17. ULB – Urban Local Body

Municipal corporations or councils responsible for governance, infrastructure, and services in cities.

18. Affordable Housing

Housing units made available at lower costs, targeted at economically weaker sections (EWS) and low-income groups (LIG).

19. EWS / LIG / MIG

- EWS – Economically Weaker Section (annual income ≤ ₹3 lakh).

- LIG – Low Income Group (₹3–6 lakh).

- MIG – Middle Income Group (₹6–18 lakh).

These categories are often used in housing policies.

20. Encroachment

Unauthorized occupation of public or private land, often the legal status of many slums in Indian cities.

21. Cluster Redevelopment

An approach where multiple adjoining slums or old buildings are redeveloped together to optimise land use and infrastructure.

22. Livelihood Linkages

Supporting employment opportunities for slum dwellers along with housing, to ensure sustainable rehabilitation.

23. Infrastructure Deficit

Shortage of basic services such as roads, drainage, sanitation, clean water, electricity, and waste management in slum areas.

24. Policy Brief

A concise document highlighting government strategies, schemes, and recommendations on slum rehabilitation for policymakers.