Water Governance in India’s Cities: From Scarcity to Security

Why urban water governance matters now

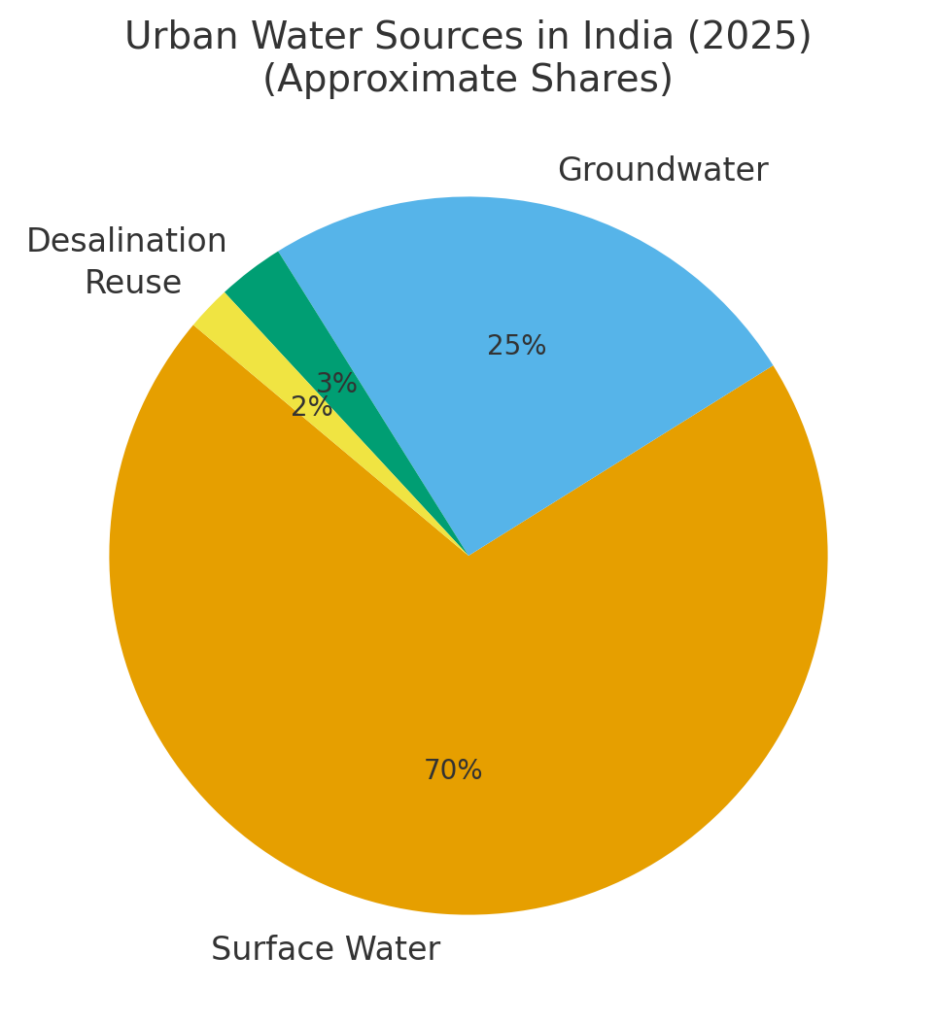

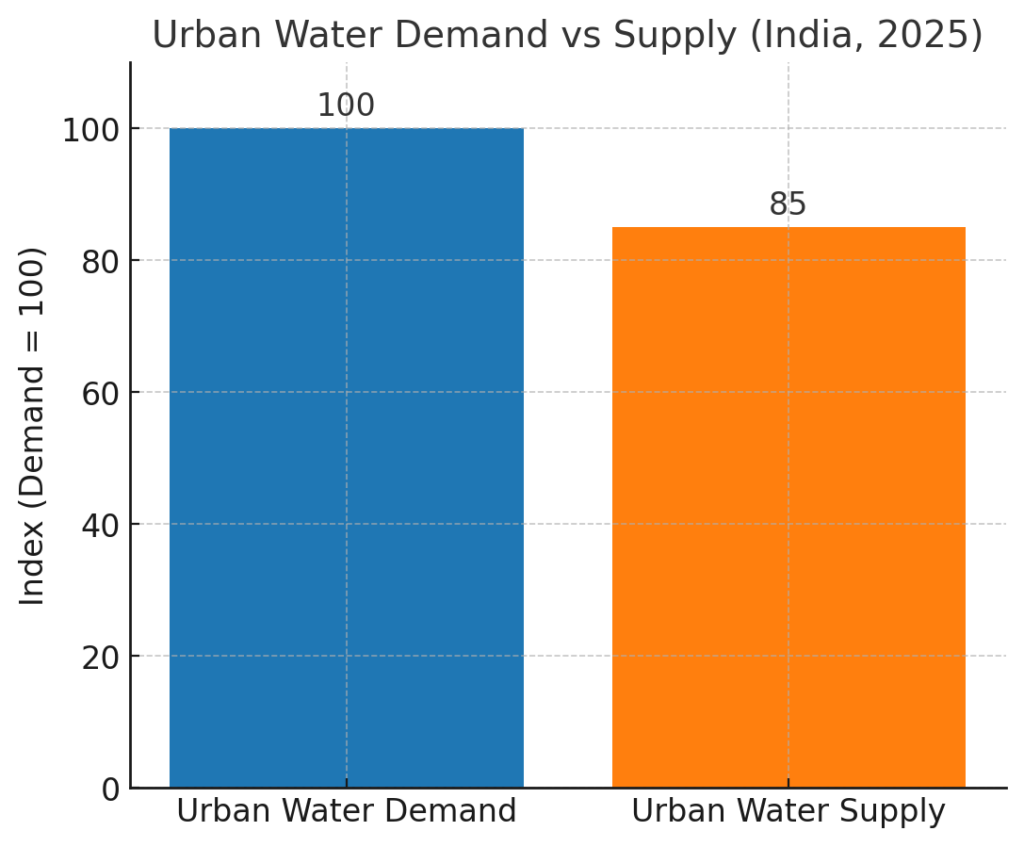

India’s cities are running out of easy water. Rapid urbanisation, climate volatility, and rising living standards are pushing demand up while groundwater tables fall and rivers choke on untreated sewage. In many metros the “last mile” of water security—reliable, safe, affordable, all-weather supply with adequate wastewater and stormwater management—depends far less on new sources than on governance: how cities plan, meter, price, recycle, regulate, finance, and engage citizens.

This essay lays out a practical roadmap for taking Indian cities from chronic scarcity to durable security. It blends current policy goals (AMRUT 2.0, CPHEEO service benchmarks, NWP 2012), emerging practices (24×7 supply, NRW reduction, reuse markets), finance tools (municipal/green bonds, PPP/HAM), and grounded case studies (Puri’s “Drink-from-Tap”, Chennai’s desalination build-out, Pune’s bonds), while being frank about gaps in treatment, reuse, and governance capacity.

1) The policy and institutional frame—who does what?

National direction, state control, local execution. Water is a state subject, but national policies set the direction. The National Water Policy (2012) calls for integrated water resources management at basin/sub-basin scale, prioritising efficiency, recycling/reuse, and creating state water regulatory authorities for rational pricing and allocation. It also emphasises volumetric supply, data transparency, and treating groundwater as a community resource rather than private property tied to land ownership. National Water Mission+2Central Water Commission+2

Urban service standards. The CPHEEO manuals and service-level benchmarking handbooks guide cities on planning and performance. They reference the widely used 135 litres per capita per day (lpcd) norm for towns with sewerage (150 lpcd for megacities), and stress comprehensive metering, quality assurance, and cost recovery. cpheeo.gov.in+2cpheeo.gov.in+2

AMRUT 2.0 (since 2021). The Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation aims 100% household coverage of functional tap connections across ~4,700 ULBs, pushes universal metering, and sets a national target to reduce non-revenue water (NRW) below 20%. It also envisages 24×7 supply (with “drink from tap” quality) and GIS-based master planning. Press Information Bureau+2Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs+2

Wastewater responsibilities. The CPCB sets standards; SPCBs enforce; cities plan and operate sewers and STPs. Yet nationally we still treat under half the sewage generated—an enormous governance and funding gap (details in Section 3). NITI Aayog

Groundwater governance. Urban and peri-urban India lean heavily on groundwater, but institutions lag. The Atal Bhujal Yojana (Atal Jal) focuses on community-led aquifer management (mostly rural, but its principles—data, participation, demand management, recharge—are vital for city regions). ataljal.mowr.gov.in+1

2) Diagnosing the urban water problem: four binding constraints

a) Supply systems leak value before they leak water

Many networks lose 30–50% of water to physical leaks and unmetered/illegal use. AMRUT 2.0’s <20% NRW targetis therefore pivotal. Achieving it needs bulk meter districts (DMAs), pressure management, active leak detection, and universal customer metering—plus the governance to bill and collect fairly. AMRUT 2.0 Collaboration Platform

b) Wastewater overwhelms cities

Urban India generated ~72,368 MLD of sewage in 2020–21, with installed capacity ~31,841 MLD and operational capacity ~26,869 MLD, leaving a large untreated gap pouring into water bodies. Recent tracking shows capacity additions lag behind rising loads. Untreated discharge impairs raw-water sources, raises treatment costs, and undermines health. India Water Portal+1

c) Groundwater depletion and contamination

Over-extraction in city regions and poor sanitation (soak pits, missing sewers) contaminate aquifers. Recent proceedings flagged Bengaluru’s eastern periphery: heavy dependence on soak pits in 110 villages threatens groundwater, while treatment capacity falls short of sewage generated. This pattern—peri-urban growth outpacing sewer expansion—is common nationwide. The Times of India

d) Climate variability

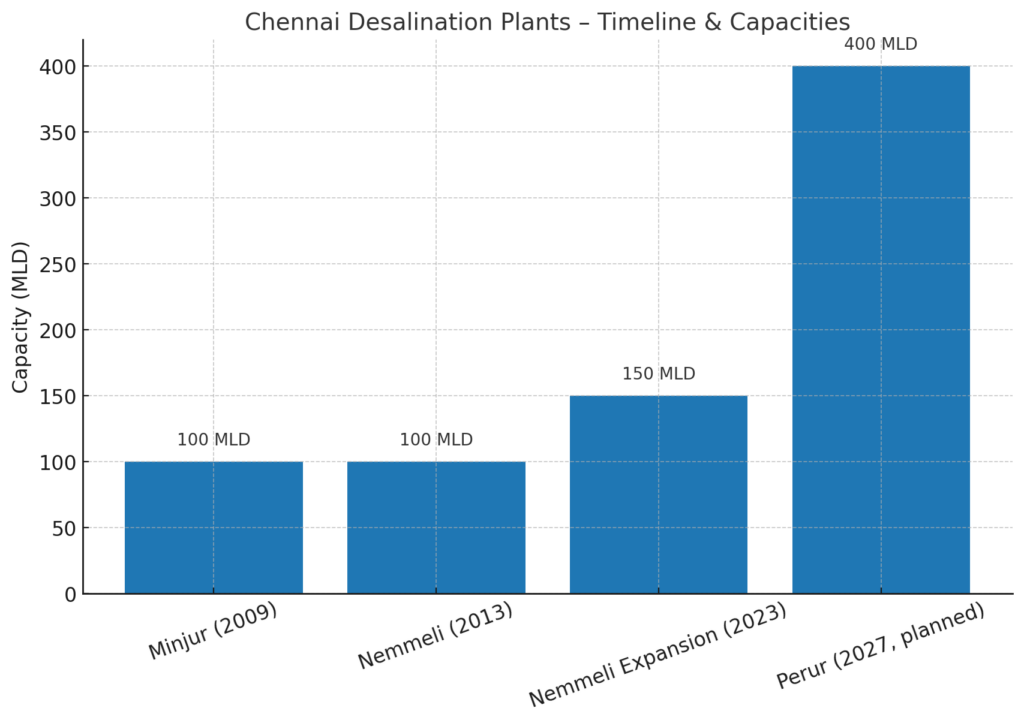

Cities face multi-year droughts punctuated by high-intensity storms. Chennai’s 2019 “Day Zero” scare accelerated desalination as a drought-proof source; the new Perur 400 MLD plant is set to become one of the largest SWRO facilities globally, adding resilience but at higher energy and lifecycle costs. SMEC

3) Where India stands today—service, treatment, and reuse

Per-capita supply. The 135–150 lpcd planning norm is entrenched, though scholars increasingly question whether such norms should be contextual to climate, density, housing typology, and reuse practices. Practically, many cities supply less than norm in summer and more than needed in monsoon, with low equity and intermittency. NCR Planning Board+1

Wastewater treatment. Even when STPs exist, missing sewer links mean sewage never reaches plants—a chronic “last-mile” governance failure. The Hindon basin example shows 953.5 MLD STP capacity vs 943.6 MLD inflow, yet only ~658 MLD is treated, with the rest bypassed due to incomplete networks and household connections. The Times of India

Reuse of treated wastewater (TWW). National frameworks emerged only recently (NMCG’s 2022 National Framework for Safe Reuse of TWW). NITI Aayog and think tanks estimate vast, untapped potential; yet less than ~3% of treated wastewater gets beneficially reused in many states. Where mandates exist (e.g., Gujarat’s policy for industries and power plants to substitute TWW), uptake improves. Mongabay-India+3NITI Aayog+3CEEW+3

4) The building blocks of urban water security

A. Demand management, metering, and tariffs

- Universal metering (bulk + consumer) is non-negotiable for 24×7 supply, NRW control, and fair tariffs. District metered areas (DMAs) enable leak localisation and pressure optimisation—core to meeting AMRUT 2.0’s <20% NRW target. AMRUT 2.0 Collaboration Platform

- Volumetric, rising-block tariffs should recover O&M while protecting the poor. The NWP 2012 endorses rational pricing and water regulatory authorities; several states have set them up for power and irrigation—urban water should follow. Central Water Commission

- Smart billing and grievance redressal—citizens pay if service is reliable, water is safe, and bills are accurate. CPHEEO’s SLB framework stresses these as governance outcomes, not mere engineering add-ons. cpheeo.gov.in

B. Source diversification and climate resilience

- Surface-groundwater conjunctive use at basin scale, with managed aquifer recharge in monsoon months and calibrated extraction in summer, reduces risk. Atal Jal’s community-led aquifer management offers a template for peri-urban belts that feed cities. ataljal.mowr.gov.in

- Desalination for coastal metros is drought-proof but energy-intensive; it belongs as a peaking or supplemental source paired with renewables and strict cost control. Chennai’s Perur 400 MLD addition is emblematic of a resilience-first strategy post-drought. SMEC

- Urban rainwater/stormwater: sponge-city style design (permeable pavements, green roofs, detention basins) reduces flooding and recharges aquifers. State bylaws should embed enforceable rainwater harvesting plus roof and plot-level storage, integrated with city stormwater master plans.

C. From “used water” to a circular economy

- Close the sewer network gap. Capital often goes into STPs, but sewers/house connections lag. Hindon basin numbers show that untreated sewage persists despite adequate treatment capacity—the prime fix is governance of network completion and O&M. The Times of India

- Mandate reuse at scale. National direction (NMCG 2022) and state policies should converge on clear off-take mandates (e.g., power plants, construction, parks, industrial estates) and quality-fit-for-purpose standards. Industrial estates near cities should be “zero freshwater growth” zones, substituting TWW for non-potable demand. NITI Aayog

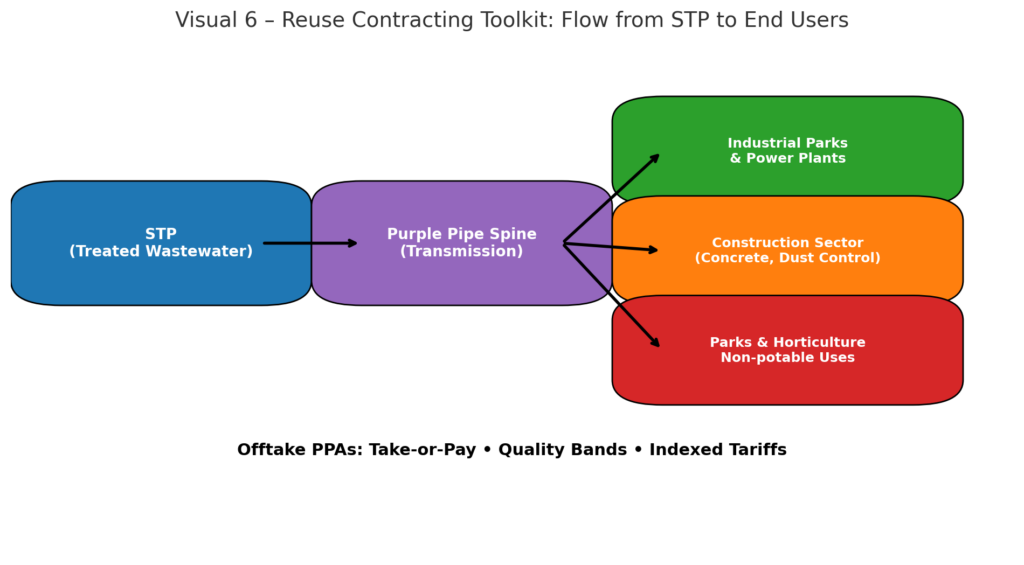

- Create markets and contracts. NITI Aayog has proposed water trading/credit-like mechanisms for TWW; cities can sign long-term offtake PPAs for reuse (cooling towers, construction, horticulture), stabilising revenue for utilities. NITI Aayog

- Regulatory nudges. CPCB guidelines for reuse, sludge management SOPs, and state mandates (e.g., Gujarat) are practical levers. Where cities set 20%+ reuse targets with compliance monitoring, reuse scales noticeably. Central Pollution Control Board+2Central Pollution Control Board+2

D. 24×7 supply as a governance upgrade, not just a pressure upgrade

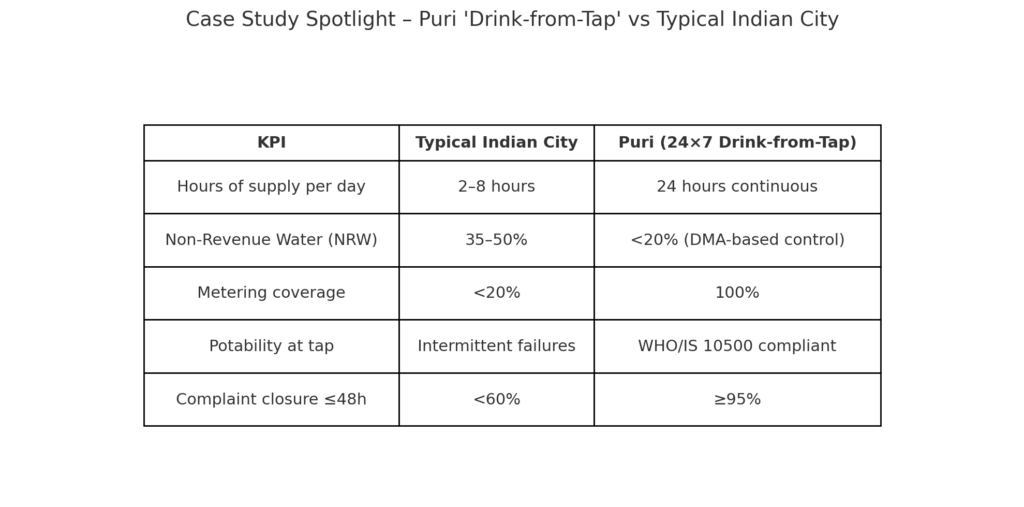

Puri (Odisha) implemented a 24×7 “Drink from Tap” program with continuous supply and certified quality at stand-alone taps—proof that Indian cities can deliver world-class service with the right mix of network rehab, metering, and O&M culture. The model hinges on DMA-based control, water safety plans, and strong communication. Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs+2PPPinIndia+2

Contrast this with piecemeal projects where network works, metering, and financing are out of sync; Pune’s ambitious 24×7 project, funded partly through municipal bonds, has faced delays in reservoirs and connections—illustrating the risks when execution capacity, land, and finance cadence don’t align. The Times of India+1

5) Financing the transition

A. Capital needs and instruments

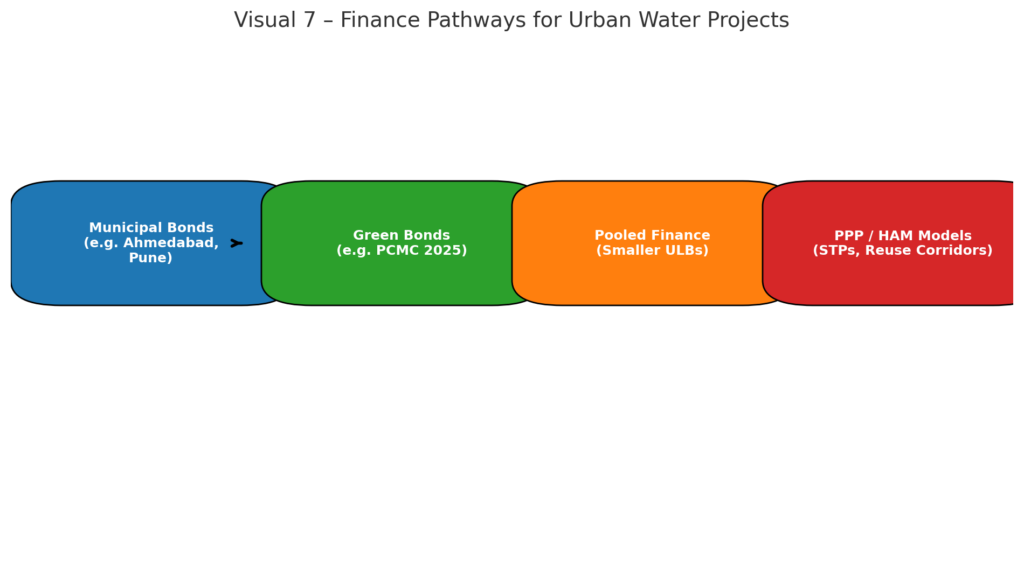

- Municipal bonds and pooled finance. Ahmedabad pioneered India’s first state-guarantee-free municipal bond (1998) to fund water and sewerage; its recent green bond (2021) saw 5.4× oversubscription—showing investor appetite when fundamentals are strong. stellenboschheritage.co.za+1

- Project-linked bonds. Pune (2017) raised ₹200 crore at ~7.5–7.6% as the first in the SEBI-rebooted muni bond era to finance 24×7 water; planned issuances totalled ₹2,264 crore. Execution delays underline the importance of robust DPRs, escrowed revenues, and phased milestones. Hindustan Times+2ORF Online+2

- Green bonds. More ULBs are tapping green muni bonds for climate-aligned infrastructure (PCMC’s 2025 raise shows the trend). Reuse projects and energy-efficient STPs are strong green candidates. The Times of India

- PPP/HAM for wastewater. The Hybrid Annuity Model, successful in Ganga STPs, is spreading to state wastewater policies (e.g., Rajasthan’s 2025 amendments), blending capital grants with annuity-based O&M performance payments—ideal for lifecycle outcomes. The Times of India

B. Revenue model and affordability

Cost recovery must cover O&M, energy, and asset depreciation, while lifeline blocks and targeted subsidies protect the poor. CPHEEO’s SLBs and NWP principles support volumetric pricing, reuse revenues (sale of TWW), and non-tariff income (connection fees, developer charges). cpheeo.gov.in+1

6) Digital utilities: data as the new water

SCADA/IoT, AMI, GIS. Real-time monitoring of flows, pressures, and quality in DMAs—paired with AMI smart meters—allows predictive leak maintenance, equitable pressure zones, and quality alerts. AMRUT 2.0 explicitly pushes GIS-based master planning and continuous monitoring as part of the shift to 24×7, “drink-from-tap” service. Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs

Public dashboards. NWP 2012 urges transparent hydrological data. Utilities should publish service KPIs (hours of supply, residual chlorine, turbidity, NRW, complaints resolved) and TWW reuse volumes; data trust builds tariff trust. Central Water Commission

7) Governance mechanics that actually move the needle

A. City Water Security Plans (CWSPs)

Each city should adopt a time-bound CWSP with five pillars:

- Demand discipline: universal metering, volumetric lifeline tariffs, targeted subsidies, and aggressive leak control (to hit NRW <20%). AMRUT 2.0 Collaboration Platform

- Source resilience: conjunctive use, watershed protection, and clear drought operating rules; coastal cities add desalination with renewable PPAs to de-risk energy costs. SMEC

- Used-water circularity: 100% household connections to sewer or FSSM; enforce reuse off-take; standard contracts for TWW to industry, parks, and construction. The Times of India+1

- Stormwater and flood risk: sponge-city retrofits and lake rejuvenation integrated with master plans.

- Open data and citizen centricity: service charters, dashboards, and grievance redressal SLAs (CPHEEO SLBs). cpheeo.gov.in

B. Regulatory architecture

State Water Regulatory Authorities (or dedicated urban water regulators) should be empowered to set tariff principles, service standards, and periodic reviews, consistent with NWP 2012. Where established, they can also approve reuse tariffs, enabling TWW to compete with subsidised freshwater. Central Water Commission

C. Institutional capacity and professional utilities

Create ring-fenced city water utilities with professional boards, performance-linked contracts, and predictable O&M budgets. Where ULBs lack depth, adopt city or state-level utilities (or cluster models) for economies of scale, with third-party O&M under clear KPIs (continuity, quality, NRW, energy kWh/kl, reuse kl/day).

D. Planning norms that reflect reality

Replace one-size lpcd norms with contextual service standards: climate-adjusted demand, building typologies, dual-plumbing for non-potable water, and fit-for-purpose quality bands. The scholarship questioning blanket norms is timely: it pushes cities toward performance-based targets—continuity, equity, potability—over raw lpcd. India Water Portal+1

8) Case studies—what’s working, what to learn

Puri, Odisha: 24×7 “Drink-from-Tap”

- What changed: Network rehabilitation with DMAs, 100% metering, real-time monitoring, water safety plans, and consistent chlorination.

- Outcome: Certified tap water quality and uninterrupted service—rare in India and replicable.

- Lesson: 24×7 is a governance package—you cannot skip metering or O&M culture and expect results. Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs+1

Chennai: desalination as climate hedge

- What changed: After the 2019 crisis, Chennai doubled down on desalination (Perur 400 MLD), alongside existing Minjur and Nemmeli plants, to drought-proof supply.

- Outcome: Greater source reliability, at higher energy and brine-disposal costs; the city is pairing supply augmentation with network improvements.

- Lesson: Desal is a resilience premium—pair with efficiency (NRW cuts), reuse (to lower raw-water demand), and renewable energy to manage lifecycle cost and carbon. SMEC

Hindon River Basin (UP): capacity without connections

- What changed: Significant STP capacity exists on paper.

- Outcome: 285 MLD of sewage still flows untreated due to missing sewers and household links.

- Lesson: Last-mile governance (connections, O&M, enforcement) is more decisive than building more plants. The Times of India

Pune & Ahmedabad: capital market access

- What changed: Pune tapped muni bonds for its 24×7 project; Ahmedabad has a long history of bonds, including a successful green bond.

- Outcome: Investor appetite exists; execution discipline is the difference between success and slippage.

- Lesson: Pair bonds with escrowed user revenues, strong DPRs, milestone-based disbursement, and transparent reporting to sustain market trust. Hindustan Times+1

9) Reuse at scale: the fastest new “source” of urban water

The opportunity. NITI Aayog and CEEW estimate that irrigating with TWW can add agricultural value and ease pressure on freshwater withdrawals; industrial and municipal non-potable uses (cooling, construction, parks, flushing) can absorb large volumes, especially in water-stressed basins. NITI Aayog+1

The policy spine is forming. The 2022 National Framework for Safe Reuse of TWW provides model state policies and standards; CPCB’s guidelines and state mandates (e.g., Gujarat) create demand. Still, reported reuse remains low single digits nationally, implying execution gaps in pipelines, contracts, pricing, and quality assurance. NITI Aayog+2Central Pollution Control Board+2

What cities should do—now:

- Map demand for non-potable water (industrial estates, power plants, construction hotspots, rail yards, parks, large campuses).

- Build purple-pipe spines from STPs to demand clusters; standardise offtake contracts with escalation clauses and quality bands.

- Set reuse tariffs below delivered freshwater (but above O&M), index them to energy costs, and guarantee minimum offtake to de-risk utility revenue.

- Disclose monthly reuse volumes on public dashboards.

10) Equity, health, and inclusion

Lifeline supply and public taps must be guaranteed for all households—slum and rental families cannot be left behind. Formalising connections in informal settlements improves both equity and utility revenue. CPHEEO’s SLBs and Puri’s example show that transparency (water quality at tap) builds citizen trust even as tariffs shift to volumetric billing. cpheeo.gov.in+1

Sanitation-aquifer link. The Bengaluru case warns that soak pits + high density = contaminated aquifers. Urban FSSM (faecal sludge and septage management) programs, desludging schedules, and co-treatment at STPs are essential in wards without sewers. The Times of India

11) A pragmatic 7-year action plan (FY2026–FY2032)

- Universal metering & NRW to <20%.

- Create DMAs citywide; bulk and consumer meters in two years; leak detection crews; pressure management; analytics for night flow.

- Tie contractor payments to NRW KPI achievements (quarterly audits). AMRUT 2.0 Collaboration Platform

- 24×7 in priority zones, scaling outward.

- Start with the most hydraulic-ready 25–30% of the city; replicate Puri-style water safety plans; certify “drink from tap” quality. Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs

- Finish the sewers, not just the STPs.

- Front-load household connections (subsidy + enforcement); publish ward-wise connection dashboards; adopt PPP/HAM for lifecycle O&M. The Times of India+1

- Reuse to 25–30% of supply by 2032.

- Publish a city reuse mandate aligned with the 2022 framework; build purple-pipe corridors to industrial clusters and parks; standardise offtake contracts. NITI Aayog

- Stormwater & sponge city.

- Retrofit high-flood zones with detention parks, bioswales, and permeable streets; make rainwater harvesting verifiable at building completion and periodically thereafter.

- Finance at scale.

- Issue investment-grade municipal/green bonds with escrowed revenues, robust DPRs, and third-party monitoring; package smaller ULBs into pooled finance vehicles; leverage viability gap funding for reuse pipelines. Publish quarterly investor reports (KPI-linked). cwas.org.in

- Regulation & data.

- Empower state water regulators to set tariff principles and reuse pricing; require city water dashboards(supply hours, quality, NRW, reuse volumes, complaint redressal). Central Water Commission

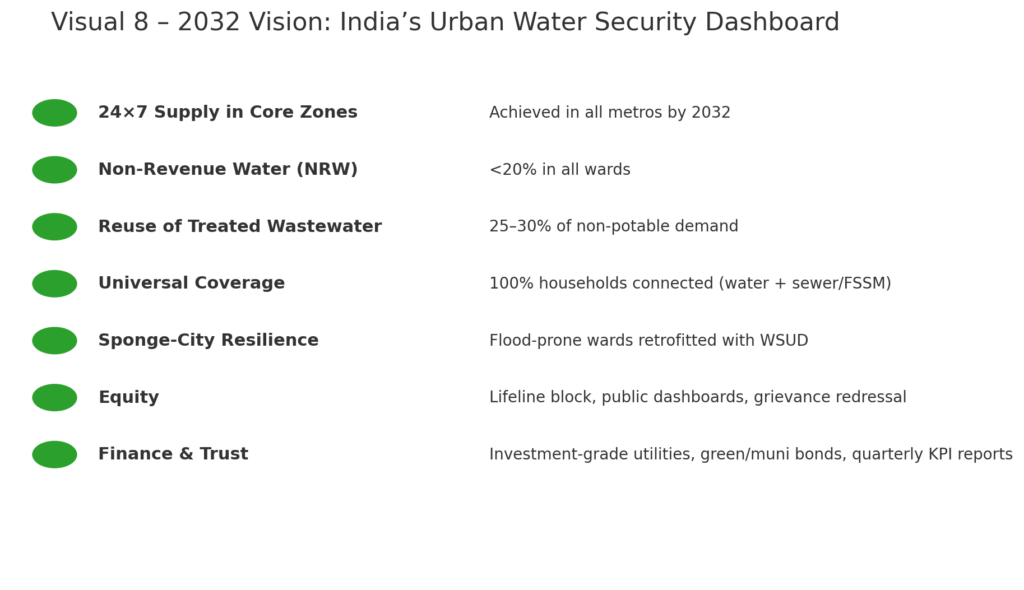

12) What success looks like in 2032

- Continuity & quality: 24×7 supply in all core zones; certified potability at tap.

- Efficiency: NRW <20% in all wards; energy use per kl drops with pressure management and pump scheduling. AMRUT 2.0 Collaboration Platform

- Circularity: ≥25% of city demand met through TWW reuse for non-potable needs; sludge safely managed and valorised. NITI Aayog

- Equity: 100% household connections (water + sewer/FSSM), lifeline blocks protected.

- Resilience: Diversified sources (surface/groundwater, rain, desal where justified), sponge-city infrastructure, and drought/heat-wave operating rules.

- Finance & trust: Investment-grade utilities with transparent dashboards and regular KPI-linked investor disclosures.

13) Risks to watch—and how to manage them

- Tariff politics vs. cost recovery. Pair tariff reforms with visible service upgrades (continuity, quality); earmark lifeline subsidies; communicate O&M + depreciation needs openly. Regulators can depoliticise decisions. Central Water Commission

- Capex without connections. Do not commission new STPs without verified sewer and household connections; deploy connection task forces ward-wise. The Hindon experience is the cautionary tale. The Times of India

- Desal cost and brine risks. Use renewable PPAs, recover energy from pressure exchangers, and enforce brine dispersion standards; treat desal as supplemental, not the base. SMEC

- Groundwater over-reliance. Adopt aquifer management plans with extraction caps, recharge projects, and real-time monitoring; extend Atal Jal-style community participation into peri-urban belts. ataljal.mowr.gov.in

- Institutional churn. Stabilise utility leadership; embed contracts with KPI-based payments and dispute-resolution mechanisms (independent engineers, escrow).

- Compliance fatigue on reuse. Move from ad-hoc pilots to mandatory offtake corridors and standard contracts, backed by CPCB/SPCB monitoring and public dashboards. Central Pollution Control Board

14) The governance mindset shift

“Scarcity to security” is not a single mega-project; it’s a management system:

- Measure everything (bulk, network, customer, quality).

- Fix the losses before adding sources.

- Connect households and bill fairly for what is used.

- Treat and reuse at scale, with contracts and pipelines, not just policies.

- Publish performance and engage citizens continuously.

- Match finance with credible projects and professional O&M.

India’s cities can deliver safe, continuous, equitable water. We have the policy compass, replicable models (Puri), and financing tools (bonds, PPP/HAM). The distance to security is a matter of disciplined execution.

References (selected)

- AMRUT 2.0: Objectives, NRW <20% target; 24×7 “drink from tap” and GIS master plans. Press Information Bureau+2AMRUT 2.0 Collaboration Platform+2

- CPHEEO & Service Benchmarks: SLBs, per-capita norms (135–150 lpcd). cpheeo.gov.in+2cpheeo.gov.in+2

- National Water Policy (2012): IWRM, reuse as the norm, pricing/regulation principles. National Water Mission+1

- Urban wastewater gap: CPCB/NITI estimates; treatment capacity and operational gaps. India Water Portal+1

- Puri 24×7 Drink-from-Tap: Case study and CPHEEO best practice notes. Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs+1

- Desalination for Chennai (Perur 400 MLD): Project overview and rationale post-2019 drought. SMEC

- Hindon basin—sewers missing despite STPs: NGT-tracked performance data. The Times of India

- Bengaluru peri-urban groundwater risk (soak pits): NGT observations. The Times of India

- Reuse frameworks: NMCG’s 2022 national framework; NITI/CEEW analyses; CPCB reuse guidelines; state mandates (e.g., Gujarat). Mongabay-India+3NITI Aayog+3CEEW+3

- Financing: Ahmedabad’s muni and green bonds; Pune’s 24×7 bonds; pooled finance and green muni trends. stellenboschheritage.co.za+2cwas.org.in+2