Transit-Oriented Development (TOD): Making Indian Cities Walkable & Liveable

Introduction

India is undergoing a rapid urban transformation. By 2036, nearly 40% of its population is expected to reside in cities, putting immense pressure on urban infrastructure, mobility systems, and housing. Against this backdrop, Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) emerges as a powerful urban planning model designed to promote sustainable, compact, walkable, and transit-served neighbourhoods.

TOD is not merely about mass transit — it’s about reorganizing urban growth around public transportation to create more liveable, efficient, and inclusive cities. For a densely populated and diverse country like India, adopting TOD offers the opportunity to correct past planning errors, reduce carbon emissions, enable inclusive growth, and boost quality of life.

1. What is Transit-Oriented Development (TOD)?

TOD refers to high-density, mixed-use development within walking distance (typically 400–800 meters) of a transit station — whether metro, suburban rail, BRTS (Bus Rapid Transit System), or multimodal hubs. It prioritizes people over vehicles, with a focus on public spaces, pedestrian paths, and non-motorized transport (NMT).

Core Principles of TOD:

- Walkability: Safe, shaded, and continuous pathways for pedestrians.

- Mixed Land Use: Integration of residential, commercial, and institutional land uses.

- Density: Higher Floor Area Ratios (FARs) near transit nodes.

- Connectivity: Seamless integration of various transit modes.

- Inclusivity: Affordable housing and accessibility for all.

- Public Realm: Plazas, parks, and active street fronts.

TOD is sometimes referred to as “horizontal skyscrapers” — cities expanding not outward, but upward and inward, clustered around transit nodes.

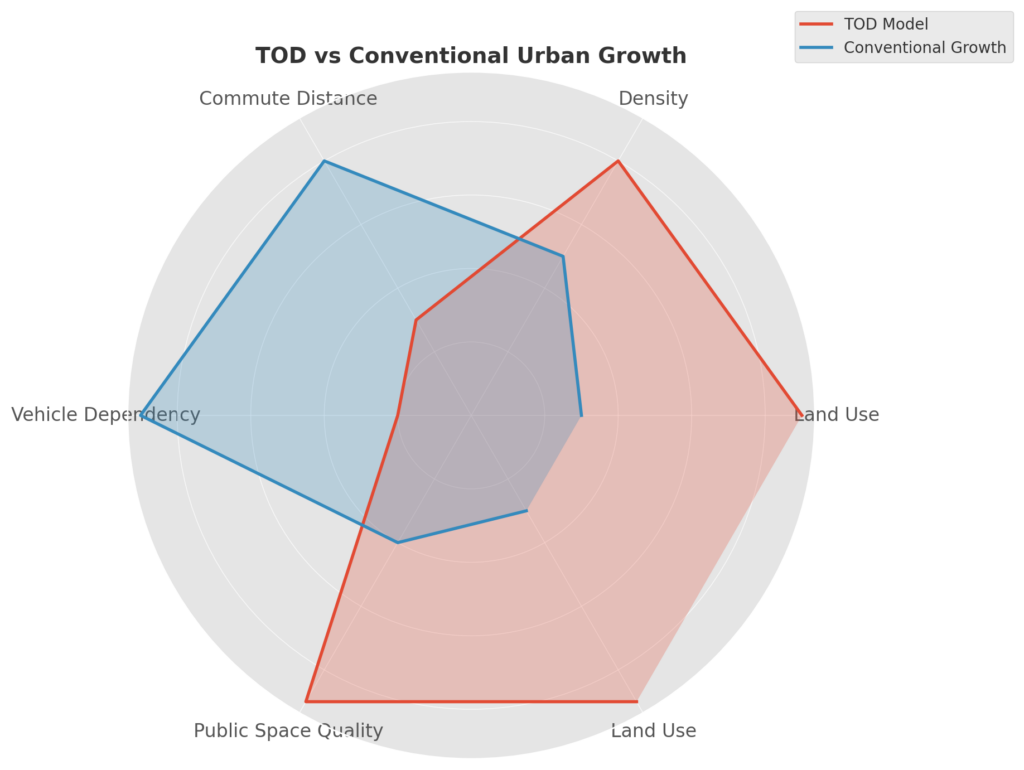

2. The Need for TOD in India

Indian cities are grappling with urban sprawl, rising vehicular congestion, air pollution, and inequitable access to mobility. Poor land use planning has led to haphazard development, longer commute times, and declining quality of urban life.

Key Challenges:

- Average daily commute in Indian metros is over 90 minutes.

- Only ~18% of urban residents live within 500 meters of a transit station.

- Over 50% of city trips are made via personal motorized vehicles.

- Urban transport contributes nearly 10% to India’s CO₂ emissions.

TOD addresses these by:

- Shortening travel distances.

- Reducing private vehicle dependency.

- Promoting compact city growth.

- Integrating housing and jobs near transport hubs.

3. Evolution of TOD in India

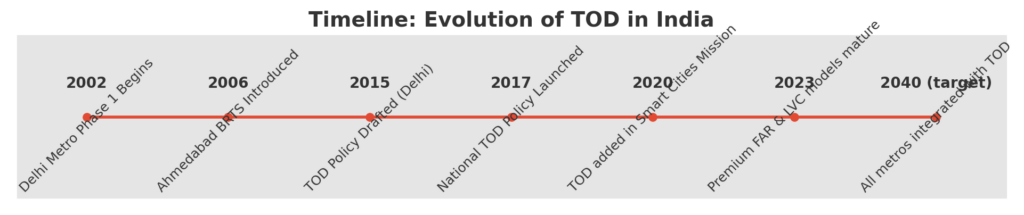

Initial Phase (2000–2010):

Indian cities began investing in metro systems (Delhi Metro, Bangalore Metro) but without integrated land use planning. Transit and real estate developed independently.

Mainstreaming TOD (2015 onwards):

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) formally adopted TOD under the National Transit-Oriented Development Policy (2017), making it integral to projects under:

- Smart Cities Mission

- AMRUT (Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation)

- Metro Rail Policy (2017)

- Urban Street Design Guidelines

TOD has since become a prerequisite for availing central funding for metros and large urban infrastructure.

4. Components of TOD in the Indian Context

a) Land Use Reforms

- Higher Floor Area Ratio (FAR) near stations (up to 4 in Delhi’s TOD zones)

- Mixed land use to reduce trip distances

- Inclusion of low-income and rental housing

b) Public Transport Infrastructure

- Metro rails (Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Chennai)

- Suburban rail (Mumbai, Kolkata, Hyderabad)

- BRTS (Ahmedabad, Indore, Pune)

- Feeder buses, e-rickshaws, and bike-sharing

c) Urban Design

- Street-level activity, shaded walkways

- Reduced parking minimums

- Multi-use plazas and green spaces

d) Regulatory Tools

- TOD Zone declarations

- Development Control Regulations (DCRs)

- Premium FAR incentives

- Land Value Capture (LVC) tools

e) Social Equity

- 20–25% of FAR reserved for EWS (Economically Weaker Sections)

- Public housing built along transit corridors

5. Notable TOD Projects in India

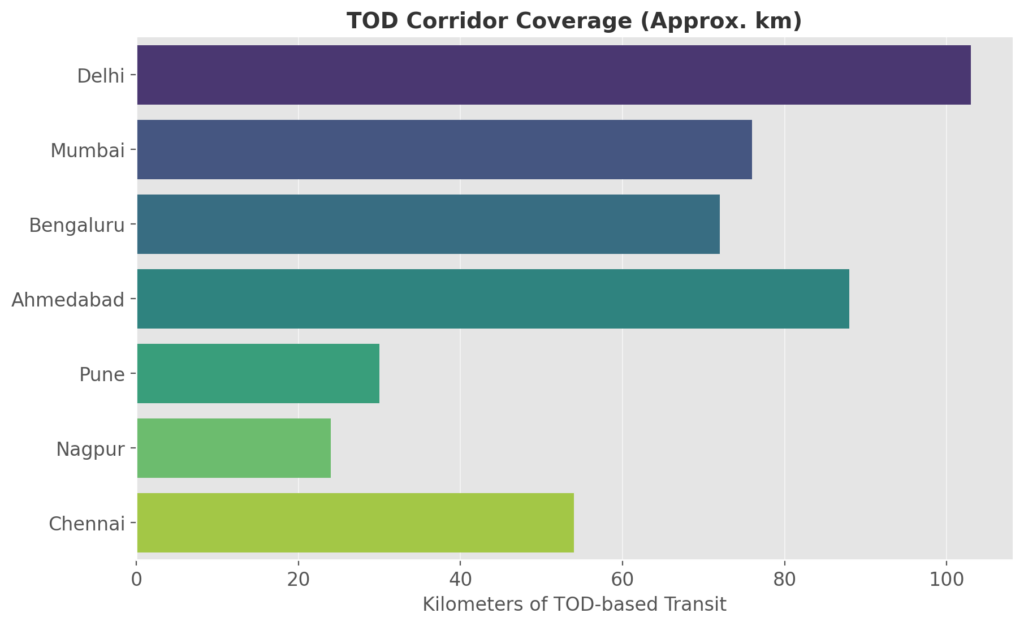

a) Delhi: India’s Flagship TOD Initiative

- TOD zones along the 103-km Delhi Metro Phase III

- Implementation in Karkardooma — high-rise mixed-use towers built on DDA land near the metro

- DDA TOD Policy: Encourages private participation through higher FAR and faster approvals

b) Ahmedabad: Janmarg BRTS

- Promoted walkable precincts and cycle tracks along the 88-km BRTS corridor

- Mixed land use encouraged near BRT stations

- Integrated mobility with affordable housing and street-level commercial development

c) Mumbai: Metro Line TOD Strategy

- MMRDA has integrated TOD strategies for new metro lines, especially Line 2 and Line 7

- Use of TDR (Transfer of Development Rights) and Premium FAR to finance metro construction

d) Bengaluru: Namma Metro Expansion

- Revised zoning and building norms for areas along Phase II

- Plans for walkable catchment zones around 60+ new metro stations

e) Pune & Nagpur

- Pune Metro TOD Policy (2018) covers all 30 km of proposed routes

- Nagpur integrates TOD with street vending, bus terminals, and heritage conservation

6. International Comparisons

India can draw valuable lessons from the successful TOD implementation in global cities:

| Country | City | Features of TOD Implementation |

| Japan | Tokyo | Dense mixed-use around rail stations, reliable last-mile connectivity |

| South Korea | Seoul | Integrated fare systems, commercial zones built atop stations |

| USA | Portland | Zoning for walkable neighbourhoods, LRT with park-and-ride and bike paths |

| Brazil | Curitiba | BRT-centric TOD, green corridors, integrated planning since the 1970s |

| France | Paris | Focus on bike lanes, pedestrianised inner cities, TOD along tram and metro |

| China | Shanghai, Beijing | Massive TOD rollouts around high-speed rail and metro hubs, real estate tied to transit revenue |

India is at an inflection point: the country still has the potential to avoid car-dominated growth and replicate these TOD practices by integrating land use and transport planning.

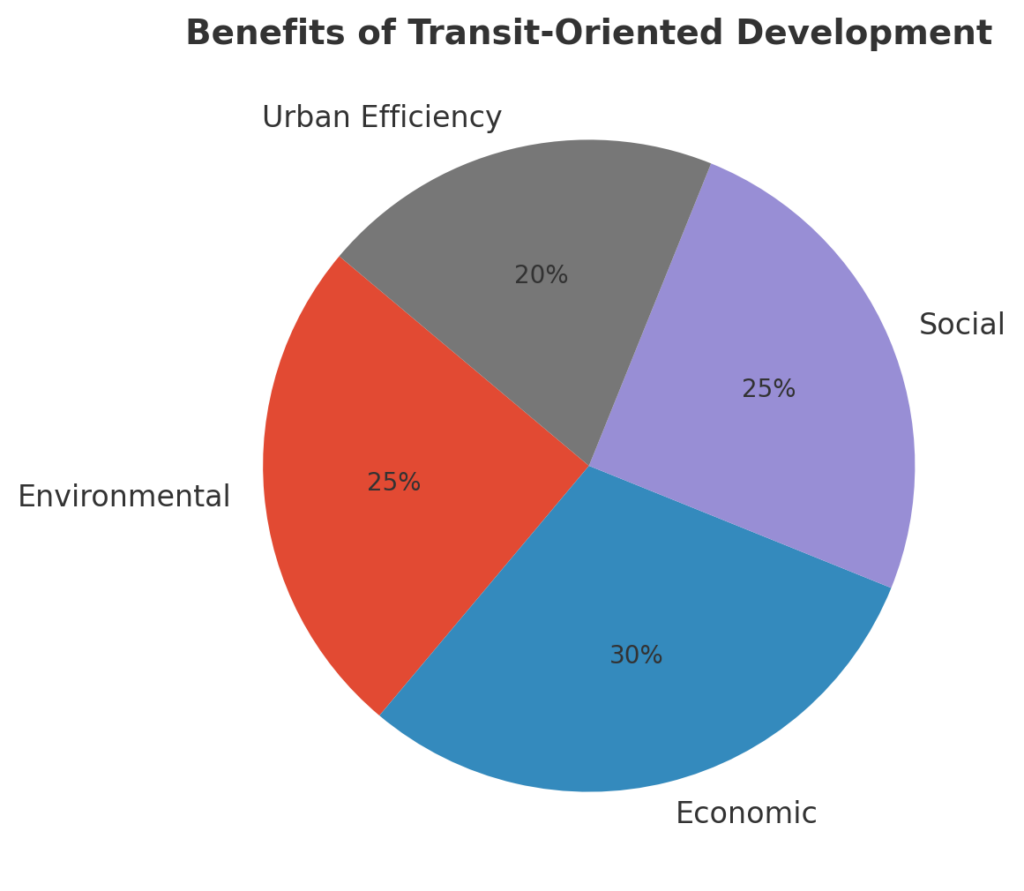

7. Benefits of TOD in Indian Cities

a) Environmental Benefits

- Reduction in vehicular emissions (up to 30% per commuter in TOD zones)

- Lower urban sprawl, preservation of agricultural lands

- Promotion of green mobility (cycling, walking)

b) Economic Benefits

- Increased property values near stations

- Land Value Capture for funding infrastructure

- Reduced fuel import bills due to modal shift

c) Social Benefits

- Better access to jobs, education, and health for all income groups

- Reduced household transport costs

- Improved gender safety due to active public spaces

d) Urban Efficiency

- Compact growth = lower infrastructure costs per capita

- Efficient water, sanitation, waste, and power services

- Revitalization of brownfield land near old transit lines

8. Barriers to TOD Implementation in India

Despite a strong policy push, implementation of TOD in India faces several challenges:

a) Institutional Fragmentation

- Land use (municipalities) and transport (metro corporations, state transport) often operate in silos

- Lack of unified metropolitan planning bodies

b) Financing Constraints

- High cost of infrastructure upgrades, especially for last-mile connectivity

- Inconsistent Land Value Capture mechanisms

c) Land Acquisition & Legal Issues

- Fragmented land holdings, litigations, and slow approvals

- Inadequate slum rehabilitation in potential TOD zones

d) Lack of Local Capacity

- Urban local bodies lack planning and execution expertise

- Private developers focus more on car-oriented gated enclaves

e) Public Resistance

- Local opposition due to fears of overcrowding or gentrification

- Inadequate communication about TOD benefits

9. Cost Considerations

Capital Investment:

TOD implementation requires upfront investment in:

- Mass transit (₹300–800 crore/km for metros)

- Footpaths, cycle lanes, landscaping (₹5–15 crore/km)

- Station area upgrades (₹20–50 crore/station)

- Affordable housing subsidies

Operating Costs:

- Maintenance of public spaces

- Fare subsidies to promote public transit ridership

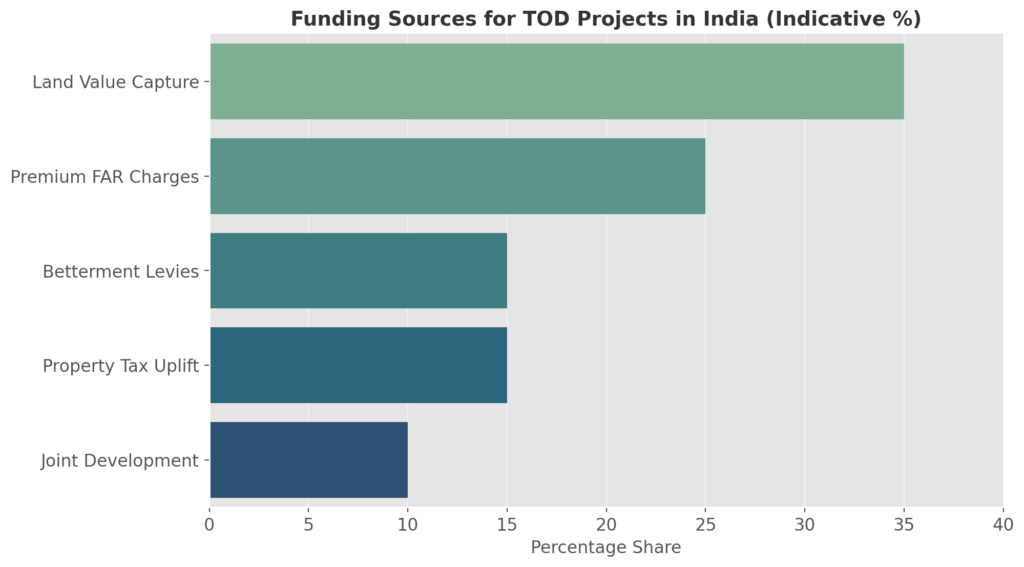

Revenue Mechanisms:

- Land Value Capture (LVC): Charges on increased FAR

- Development Premiums: Additional FAR sold to private developers

- Property Tax Increments: Near TOD corridors

- Joint Development: Metro station air rights (e.g., DMRC malls)

10. Lessons from Developed and Developing Economies

Policy Alignment:

- Japan: Integration of rail companies and real estate arms

- France: Regional transit and land use bodies (e.g., Île-de-France Mobilités)

- Colombia: Bogotá uses LVC and public-private partnerships for BRT & TOD

Planning Tools:

- Parcel-based GIS mapping for station catchments

- Mandatory TOD zones in Master Plans

- TOD Impact Assessment reports before project approvals

Public Engagement:

- US cities like Denver involve communities early in TOD planning

- Citizen design workshops and walk audits improve acceptance

India needs to adapt these tools to local contexts while strengthening institutional coordination and public awareness.

11. Making TOD Work for Indian Cities: Way Forward

a) National-Level Actions

- Update Model Building Bye-Laws (MBBL) to mandate TOD norms

- Incentivise states via AMRUT and Smart Cities funding

- Create a dedicated TOD Mission under MoHUA

b) State & ULB-Level Interventions

- Declare TOD Zones with clear DCRs

- Mandate mixed-income housing (e.g., 20% EWS units)

- Build multimodal transit hubs with seamless pedestrian connectivity

c) Infrastructure & Design

- Prioritize last-mile connectivity (e-buses, cycling, shaded walks)

- Universal design for differently abled and elderly

- Mixed-use streets with active frontages

d) Institutional Coordination

- Set up Unified Metropolitan Transport Authorities (UMTAs)

- Empower SPVs (e.g., Bengaluru Smart City Ltd) to execute TOD projects

- Train city planners in TOD and sustainable urban design

e) Financing Mechanisms

- Value Capture Finance: FAR premiums, betterment levies

- Public-private partnerships for station area development

- Use of green bonds for funding non-motorized transport infra

12. Future Outlook: Indian Cities in 2040

By 2040, if implemented at scale, TOD can transform Indian cities into inclusive, green, and vibrant urban hubs. The focus must shift from car-centric cities to people-centric ones. A city like Pune or Jaipur, with well-planned TOD corridors, can rival the liveability of Copenhagen or Seoul — not by replicating their architecture, but by embracing their principles of connectivity, density, and dignity in public space.

Conclusion

Transit-Oriented Development is not a silver bullet, but it is one of the most effective tools available to reimagine urban growth in India. With strong political will, citizen participation, and planning discipline, TOD can be India’s pathway to walkable, affordable, and climate-resilient cities. As India urbanizes, it must choose: more flyovers or more footpaths. TOD shows us the way forward — to build not just bigger cities, but better ones.

References

- Ministry of Housing & Urban Affairs (MoHUA), TOD Policy, 2017

- World Bank TOD Toolkit (India Case Studies), 2021

- NITI Aayog, “Transforming Urban Mobility,” 2020

- Delhi Development Authority (DDA) TOD Guidelines

- World Resources Institute (WRI India) – TOD Planning Reports

- Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) India Reports

- Urban Mass Transit Company Ltd (UMTC), Planning Frameworks for TOD

- Smart Cities Mission Implementation Toolkit, MoHUA

- OECD Report: “Compact City Policies – A Comparative Perspective,” 2020

- International Association of Public Transport (UITP), TOD Best Practices