Article 4 (Series on India’s Pension System): Global Pension Models, Country Examples, and Lessons for India

In the first three articles of this series, we looked at India’s pension challenge through the lenses of demographics, labour-market informality, fiscal constraints, and the design gaps in coverage and adequacy. This fourth piece steps outside India and maps how leading countries structure old-age income security, why those structures evolved, and what practical lessons India can adapt—without copying models blindly.

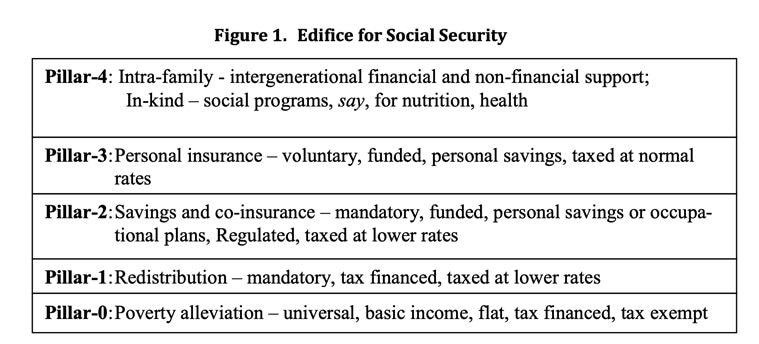

A useful way to think about pensions internationally is: most successful systems don’t rely on a single instrument. They blend (a) a basic public floor to prevent poverty, (b) an earnings-related contributory layer to protect living standards, and (c) funded savings (occupational and personal) to improve adequacy and diversify risk. This “multi-pillar” framing is widely used in global policy discussions, including the World Bank’s five-pillar approach.

1) A practical typology of pension systems used worldwide

A. “Beveridge” style: tax-funded or flat public pension + supplements (poverty prevention first)

Core idea: No elderly citizen should fall below a minimum living standard. Benefits are flat or income-tested, financed largely from taxes.

Where you see it (in different mixes):

- United Kingdom (State Pension + means-tested supports; plus workplace pensions through auto-enrolment)

- Canada (Old Age Security + income-tested Guaranteed Income Supplement)

- Nordic countries often use a strong floor plus occupational schemes.

Strengths: Simple; strong poverty reduction; fiscally controllable through eligibility age/indexation rules.

Risks: Flat benefits alone often don’t preserve pre-retirement living standards unless supplemented by occupational savings.

B. “Bismarck” style: contributory social insurance (earnings-related public pension)

Core idea: Workers and employers contribute; benefits are linked to lifetime earnings and contribution years.

Where you see it: Many continental European systems (often with additional occupational layers). OECD country notes show large diversity even within this family.

Strengths: Perceived fairness (“you get what you contributed”); broad legitimacy.

Risks: In ageing societies, pure pay-as-you-go (PAYG) designs face stress unless retirement ages and benefit formulas adjust.

C. Notional Defined Contribution (NDC): PAYG but designed like an “individual account”

Core idea: Contributions are recorded in notional accounts; benefits are calculated actuarially (often linked to life expectancy). The financing remains PAYG, but the rules automatically adjust.

Leading example: Sweden combines an NDC PAYG component with a funded component and a guarantee pension for low income.

Strengths: Automatic stabilisers; transparency; encourages longer working lives.

Risks: If wages stagnate or careers are interrupted, adequacy can suffer unless the safety net is strong.

D. Funded Defined Contribution (DC): mandatory or quasi-mandatory retirement savings

Core idea: Money is invested in funded accounts (individual or collective). Benefits depend on contributions and investment returns.

Leading examples:

- Australia’s Superannuation Guarantee (compulsory employer contributions; regulated funds)

- Singapore’s CPF (a provident fund model with mandatory contributions and administered accounts)

Strengths: Builds national savings; reduces long-run fiscal pressure; portable across jobs.

Risks: Market risk; uneven outcomes if contribution density is low; requires strong governance and low leakage.

E. Collective risk-sharing funded systems (often occupational): “CDC” / collective DC / strong social partner role

Core idea: Assets are funded, but risks are pooled collectively; benefits may be adjusted rather than guaranteed.

Iconic case: Netherlands—traditionally strong occupational pensions with near-universal coverage; now transitioning toward a DC-style framework while trying to preserve collective risk-sharing features.

Strengths: High coverage; professional management; risk pooling; typically low fees.

Risks: Complexity; transition challenges; intergenerational fairness debates (especially during reform).

F. Privatised individual-account systems (classic Latin American model) and modern “mixed” reforms

Core idea: A large share of retirement income comes from privately managed individual accounts; newer reforms add social insurance elements due to adequacy concerns.

Reference case: Chile pioneered mandatory individual accounts; later faced dissatisfaction over low payouts for many workers and began reforms to introduce more solidarity and adjust contributions.

Lesson: individual accounts alone rarely solve old-age security if careers are informal/interrupted.

2) Country snapshots: how leading systems combine the building blocks

2.1 United Kingdom: “auto-enrolment” as a coverage engine

The UK requires employers to provide a workplace pension and automatically enrol eligible employees—an elegant way to convert “intent to save” into “actual saving.”

Policy discussions now focus on expanding coverage further (e.g., younger workers and low earners), highlighting that design details matter.

What stands out for India

- Auto-defaults work: people stay enrolled once enrolled.

- Compliance + simple payroll rails are crucial.

- Helps especially when financial literacy is uneven.

2.2 Canada: strong public floor with income-tested top-ups

Canada’s public old-age architecture includes a broad base benefit and an additional income-tested supplement for low-income seniors (GIS).

In plain terms: poverty prevention is treated as a direct public responsibility, not left to market-linked savings.

What stands out for India

- A clear, rules-based old-age anti-poverty layer can reduce pressure to promise guaranteed pensions inside contributory schemes.

- Targeting (income-tested) helps fiscal sustainability, but requires good administrative capacity.

2.3 Sweden: automatic stabilisers through NDC + funded component

Sweden’s system is widely cited because the national retirement pension includes a PAYG notional accounts system (NDC) plus a mandatory funded DC piece, plus a guarantee pension for those with low lifetime income.

The architecture aims to keep the system solvent while making the link between work, contributions, and pensions visible.

What stands out for India

- The concept of transparent lifetime contribution records (even in PAYG) improves trust.

- Automatic adjustment mechanisms reduce the political cycle’s influence on pension promises.

2.4 Australia: compulsory funded savings at scale

Australia’s Superannuation Guarantee requires employers to contribute a mandated percentage to retirement savings for eligible workers.

A key feature is the systemic, payroll-embedded nature of contributions—retirement saving becomes an infrastructure, not a niche product.

What stands out for India

- When contributions are “built into payroll,” coverage can grow rapidly in the formal sector.

- But enforcement matters: unpaid contributions remain a policy focus in Australia too, reinforcing that compliance systems must be strong.

2.5 Singapore: CPF provident fund (mandatory contributions, administered accounts)

Singapore’s CPF is a mandatory savings system with age-graded total contribution rates (employer + employee) and structured accounts; the CPF Board’s overview shows how contribution rates vary by age band.

It is a classic example of a high-discipline, high-compliance provident fund.

What stands out for India

- A provident approach can create high savings rates, but it relies on:

- strong formal employment capture,

- excellent administration,

- and careful rules on withdrawals/leakage.

2.6 Netherlands & Denmark: high-coverage occupational pensions and collective arrangements

The Netherlands historically achieved exceptionally broad occupational coverage and large funded assets, with systems supported by strong institutions and governance.

Denmark’s country profile describes occupational pensions as fully funded DC schemes agreed via collective arrangements.

What stands out for India

- Institutional quality (governance, transparency, fiduciary discipline, low fees) is not optional—it is the system.

- Collective arrangements can keep costs low and risk-sharing more balanced.

2.7 Chile: why individual accounts alone can disappoint

Chile’s 1980 reform created mandatory personal accounts with private management—an influential model globally.

Yet dissatisfaction rose because many workers had interrupted contribution histories and low replacement rates. Recent reforms approved by Chile’s Congress illustrate the shift toward a more mixed/solidarity approach.

What stands out for India

- In economies with informality and contribution gaps, pure DC systems can under-deliver unless combined with:

- a strong public floor,

- incentives and defaults to raise contribution density,

- and protections for longevity/market risk.

3) Lessons for India: what to adapt (and what to avoid)

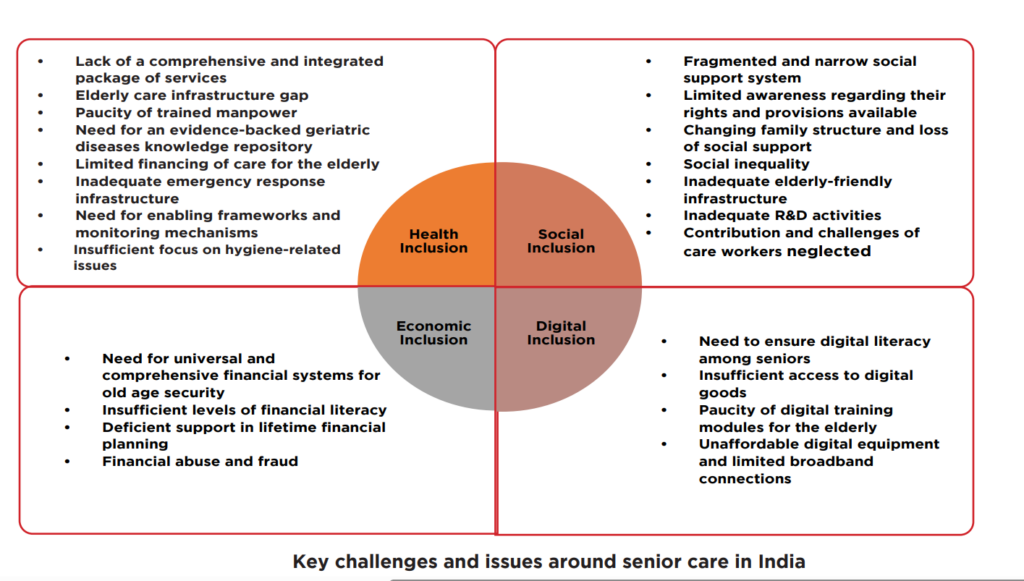

India’s pension challenge has a specific shape: a fast-growing elderly population over time, high informality, uneven ability to contribute regularly, and limited fiscal space. Therefore, the “lesson” is not one foreign template; it is how to assemble an India-suitable mix.

Lesson 1: Separate the goals—poverty prevention vs. living-standard smoothing

Leading countries implicitly separate two objectives:

- No elderly poverty (basic floor, often tax-funded or income-tested).

- Maintain reasonable living standards for those who contributed (earnings-related or funded savings).

For India, blending these two goals inside one contributory scheme often creates confusion and political risk. A clearer approach is:

- Strengthen the minimum old-age income floor (well-targeted, digitally administered).

- Use contributory schemes for the second goal (adequacy for contributors).

(World Bank’s multi-pillar thinking supports designing across pillars rather than overloading one instrument.)

Lesson 2: Defaults and payroll rails outperform “voluntary good intentions”

The UK’s auto-enrolment is a powerful demonstration that default enrolment can raise participation dramatically when employers and payroll systems are the channel.

For India:

- In the formal sector, expand defaults wherever feasible (especially for MSMEs where administrative burdens are real).

- For semi-formal and platform workers, build auto-contribution nudges into payment apps and platforms (where income is already digitised).

Lesson 3: Build “contribution density” first; returns come later

Chile’s story is a warning: even a well-designed investment account cannot compensate for missing contributions caused by informal work, unemployment, or low wages.

For India:

- Make it easier to contribute small amounts frequently.

- Reduce friction (KYC, transactions, portability).

- Reward persistence (matching contributions for targeted groups, or micro-bonuses for continuity).

Lesson 4: Use automatic stabilisers to depoliticise sustainability

Sweden’s NDC framing shows how pension promises can be aligned with demographic realities using transparent formulas and built-in adjustment mechanisms.

For India, even without full NDC adoption:

- Publish clear long-term projections,

- adopt rule-based indexation,

- and link some parameters (retirement age, accrual rates) to longevity—gradually and with protections for the vulnerable.

Lesson 5: Governance and low fees are as important as “design”

High-performing occupational systems (Netherlands/Denmark) are admired not just for benefit formulas but for strong governance, professional management, and cost discipline.

For India:

- Continue pushing transparency on charges, returns, and lifecycle outcomes.

- Strengthen fiduciary accountability and data quality (transitions are where errors and mistrust spike—Netherlands’ reform debate itself highlights this governance challenge).

Lesson 6: Keep guarantees targeted; avoid open-ended fiscal promises inside market-linked schemes

Many countries offer a public minimum rather than a guaranteed return inside contributory investment schemes—because guaranteeing market outcomes tends to create hidden fiscal liabilities.

India’s experience with multiple schemes and recent debates on assured pensions show the political demand for certainty. Recent reporting notes movement toward assured pension arrangements for some government employees, reflecting this tension.

The lesson from abroad is: if you must provide guarantees, do it transparently and budget for it—preferably in the social assistance / basic floor layer.

Lesson 7: Expand coverage with “institutional partnerships,” not only government machinery

A modern trend is to increase competition, widen distribution, and improve product reach through regulated private participation. India’s own NPS ecosystem has been evolving (including policy moves to broaden who can sponsor pension funds), which is consistent with this direction.

4) Where this fits into India’s existing pension architecture

India already has the building blocks:

- A national DC pension platform (NPS) described by the regulator as a defined contribution system with Tier I/Tier II structure.

- A defined-benefit style minimum pension promise for targeted groups under Atal Pension Yojana (APY) (with guaranteed pension amounts per rules).

What India can do, drawing from global lessons, is to make the system behave like a coherent whole:

- A clear minimum floor (simple, targeted, dignified).

- Portable contributory accounts that follow workers across employers and states.

- Default enrolment and easy micro-contributions to raise contribution density.

- Stronger governance + low fees + transparent reporting to build trust.

5) Closing Bridge for the Four-Article Series

India’s pension debate has reached a critical inflection point. The earlier articles in this series highlighted how demographic ageing, shrinking family support structures, informality in the labour market, and rising longevity are together reshaping the country’s old-age security challenge. This fourth article widened the lens to global experience—demonstrating that no major economy relies on a single pension instrument, and that successful systems are built through carefully balanced, multi-pillar architectures.

The global evidence is unambiguous. Countries that have managed ageing well have done three things consistently:

- Protected all elderly citizens from poverty through a basic public floor,

- Linked contributory benefits transparently to lifetime work and savings, and

- Used defaults, institutions, and governance—rather than pure voluntarism—to expand coverage and sustainability.

For India, the lesson is not replication, but adaptation. The country already has most building blocks in place—minimum income support, contributory pension platforms, digital infrastructure, and a growing formal–digital workforce. What is needed now is integration, clarity of objectives, and institutional discipline, so that each pension instrument does one job well rather than trying to solve all problems at once.

If India can combine a dignified old-age income floor with portable contributory savings, supported by automatic enrolment, strong governance, and fiscal realism, it can convert today’s demographic challenge into a manageable transition—without burdening future generations or undermining growth. Pension reform, in that sense, is not merely a welfare issue; it is foundational economic infrastructure for a mature and resilient India.

6) References

- World Bank. “Five Pillar Framework” (pension system design).

- OECD. Pensions at a Glance 2025 (and related country profiles).

- Government of the United Kingdom. Workplace pensions / automatic enrolment guidance.

- UK Parliament. Research briefing on automatic enrolment issues (Jan 19, 2026).

- Government of Canada. Old Age Security & Guaranteed Income Supplement.

- Australian Taxation Office. Superannuation Guarantee rates/thresholds (official rates page).

- CPF Board. CPF overview and contribution rates (updated Jan 2026).

- Swedish Pensions Agency. Overview of Sweden’s pension system.

- European Commission. Sweden pension fiche (NDC + funded DC components).

- Reuters. Coverage on Chile pension reform and India pension policy developments (contextual reporting).

- Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority. NPS overview pages.

- Ministry of Finance India. APY information pages/rules.

This article is part of a four-part series on India’s pension system, examining demographic pressures, design challenges, fiscal realities, global models, and reform pathways.

Reform Path